The Launchpad team is planning a new feature that will allow you to link bugs to each other and describe their relationship. The general idea is that you can say one bug depends of the fix of another. The goal is to make it clear where conversations to fix issues take place, who will do the work, and when the work can start.

I summarised the existing bug linking features and hacks previously. Now I want to explain the workflows and UI that Launchpad could support to create and explain relationships between bugs.

Managing bug relationships

Organisations and communities split issues into separate bugs when different people work at different times with different priorities to solve the bigger issue. Organisations and communities merge bugs when they want a single conversation to fix an issue that affects several projects at a single time. Explicit relationship between bugs (or the many projects listed on a single bug) would help projects organise work.

There are four general relationships that people try to describe when working to fix an issue. These relationship are either explicit, or implied when a bug affects multiple projects, or many bugs affect a single project. The relationship informs everyone about where the conversation to fix an issue happens, and the order of work to fix a group of issues.

- Duplicate: Bug X is the same as bug Y. The primary conversation about fixing the bug happens on bug Y. A secondary conversation happen on bug X. The affected projects, their status and importance, of bug X are identical to Bug Y.

- Dependency: Bug X depends on bug Y. Bug Y must be fixed before bug X can be fixed. The bugs have separate conversations, but each is informed of the other. Though the bugs have separate status and importance, there is some expectation that work proceeds from one bug to the next. As the bugs might affect different projects, the work to fix a bug may be done by different people. A project bug might depend on the fix in a library that is provided by another project. A bug in a distro series package might depend on the fix in an upstream project release. Dependency is implied when we see a bug that affects a distro package also affects the package’s upstream project.

- Similarity: Bug X and bug Y are caused by similar implementations. Bug X and Y require separate fixes that can happen concurrently. The bugs might share a conversation to find a fix, but the work and conversation is more often independent. In some cases, the proper fix is to create one implementation that the similar bugs depend on to fix the issue. A project might have two bugs caused by a bad pattern repeated in the code, or a pattern in one project is also used by another project. Each location of the pattern needs fixing. Maybe the right fix is to have a single implementation instead of multiple implementations.

- overlap: Fixing bug X changes the scope of work to fix bug Y. These bugs have separate conversations, but the work to fix each issue needs coordination. Fixing one bug may make the other invalid, or make it more difficult to fix the other. Maybe these bugs need to be redefined so that they do not overlap? Maybe bug X can be fixed at the same time as bug Y? Maybe both bugs really depend on an unknown root cause…bug Z?

We might imagine the relationships like sets. The duplicate bug is a subset of the master bug. Two bugs intersect in the overlap relationship. Similarity is a superset of several bugs. The dependency relationship has a direction pointing from one bug to the next.

Managing separate conversations

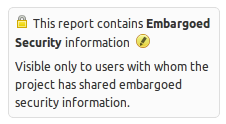

People working with proprietary information create duplicate and or dependent bugs to manage separate conversations. The “Affect project”, “Affects distro”, and “Duplicate” action do not work because they either mix conversations, or loose status and importance. Users benefit when private conversations are split from public ones, but Launchpad does not help the user do this.

Launchpad will not permit projects to share the forthcoming “proprietary” bug information type. Proprietary information is given to one project in confidence; The project cannot share that information with another project. The “Affects project”, “Affects distro” cannot add projects to the bug, so Launchpad must help users report a separate bugs.

When someone realises a private bug affects more than one project, Launchpad could help the user split the bug into separate bug reports to manage conversations and the order of work to fix the greater issue. Instead of adding a project or distro to the bug, the user might want to choose the project to report the bug in, and be prompted to revise the bug summary and description so that private information is not disclosed. The new bug is commonly public. It is the master bug, this is where the public conversation happens. This practice benefits more than the user who reported the bug…there is a public place for all users to discuss the issue.

Users are less likely to report a duplicate bug when Launchpad can show the public bug in the list of similar bugs. The principal cause of bug 434733 is not commercial projects, bug non-commercial projects like Ubuntu that mark bugs as duplicates of private bugs without consideration that users want to be informed and participate in the conversation.

Duplicate bugs continue to have separate side conversations that often focus on release issues. The discussion of how to fix the issue happens on the master bug. Duplicate bugs also have wasteful conversations that can be answered by the master bug. There is always a risk of disclosure when the reporter of a private bug has to visit the public bug to learn information that is pertinent to the private bug. The risk and inconvenience could be avoided by showing the important information on the duplicate bug — do not force users to change the context when working with private data.

We can substitute another relationship for “duplicate” in my case for separating discussions. When a fix for a bug is dependent on a one or more other bug fixes, there are several conversations with different people with different concerns. The same is true for bugs with similar or overlapping concerns. The only time conversations really need to be shared is to coordinate the timing or scope of the fixes.

While privacy is a primary reason to split conversations, splitting public conversations can benefit as well. The current UI that encourages a single conversation of ambiguously related downstream and upstream projects is a source of unwanted email. If I am only interested in the issues that affect my projects, do not make be get email for all the other projects. Splitting conversations into several bugs within a project is also a legitimate means to solve large problems that require different developers to fix code at different times. Minimising the notifications to just the relevant information keeps users focused on the issues.

Linking existing bugs

The workflow to select and link bugs is untrusted. When marking a bug as a duplicate, or linking a bug to a branch, Launchpad asks me to provide the bug number (Launchpad Id), then the page updates and I learn the consequences. Did I type the right number? Did people get emails about irrelevant or confidential information?

I expect Launchpad to ask me to review the bug I am linking and ask me to continue or cancel. Launchpad has to show enough information to answer my question’s and gain my trust:

- What is the bug’s summary?

- What is bug’s information type — is it private?

- Which projects does the bug affect?

- What are the bug’s tags?

- What is the bug’s description?

The presentation for bug listings provides most of this information. Launchpad could reuse the presentation (that I am already familiar with) when asking me to review the bug that matched the number I entered.

I imagine that if the action I am taking is specific, like marking a bug as a duplicate of another, Launchpad does not need to ask me about the relationship. In cases where the relationship is not implicit in the action, Launchpad must let me select the relationship between the bugs.

I know many users expect bug linking to work like selecting a user. They want to enter search criteria to see a listing of matches. The user might expand a match to see additional information. The user can select the bug, and maybe select the relationship to create the link. I am sceptical that this workflow would meet my needs. I often use advanced bug search to locate a bug; I cannot imagine offering advanced bug search in the small space to select a bug to link. The picker infrastructure that provides the workflows to select users and projects supports filters, which could be adapted to work with bug tags. I doubt this will be very useful. Advanced bug search does not work well across multiple projects, and bug linking does and must work across projects. I think people will still needs to use advanced search to locate the bug that they want to link.

Presenting a summary of the bug relationships

When an issue is represented by several bugs, or a bug affects several projects, users need known how they relate to understand where and when someone needs to take action. Users often open many pages because Launchpad cannot summarise the relationships between several bugs. Users will also read through long comments to learn why a bug affects many projects.

When viewing a bug, the user needs to see a listing of related bugs (dependency, similarity, and overlap). The listing summarises the affected project, status, importance, assignee, and milestone. Users might need to see bug tags, and badges for branches and patches. Maybe this is like the listing of bugs shown in bug search.

The affects table is a special bug listing. Does it need to be special? Users want to see the relationship between the items in the affects table. I want to know if the fix in a package depends on the fix in an upstream project. I am unsure how this could be done since there might be many relationships in the table. Maybe the many relationships, 3 or more affected project, packages, and series, will diminish when bug linking is available. We know that users unsubscribe when a bug affects many things because the conversation looses focus. When users can link bugs, there will be less needs to say a bug affects many things.

Privacy is a special case. A user can only see the relationship between two bugs if the user can see both bugs. When the listing contains private bugs, the presentation must call-out that they are seeing privileged information. Launchpad does not have a consistent way to show that part of a page contains private information.

- The user profile page will show locks before email addresses.

- Bug listings show a lock icon among other icons after the bug.

- Branch listings and linked branches show the lock icon after the branch.

Launchpad must make it clear to the user to not discuss the private relationships in the bug’s conversation.

Duplicates are presented differently from other bugs because they are subordinate to the master bug. There are several problems with the current presentation of duplicate bugs.

- Duplicate bugs show contradictory information in the affects table

- Duplicate bugs may not show the master bug if it is private

- Master bugs may show hundreds of duplicate bug numbers without summary or privacy information

- Why do I need to see all the duplicate bug numbers on a master bug?

Users do not need to see a list of all the duplicate bugs on the master bug. The number of duplicates is more interesting that a listing of numbers. User care about the duplicates they reported because they might want a side conversation, maybe Launchpad should show the user a link to the bug he or she reported? A contributor might want to read the the conversations in the duplicates for new information, so Launchpad does need to show a list of duplicates when the user asks for it. The listing of duplicates must indicate which are private. Other data like status and importance are irrelevant because the master bug provides the this information.

When I view a duplicate bug page, Launchpad must make it clear that this bug is a duplicate. I need to see the master bug’s information: affected project, importance, status, milestone, and assignee. I am not sure if the user should see its own affects table; that information would only be important if the bug was unduplicated.

There is a problem if the master bug is private and the user does not have permission to see the master bug. The user cannot see the master bug exists. Launchpad could prevent duplicate master bugs from being private if the project can have public bugs. In the case of projects with default proprietary bugs, the master bug will always be private. When the reporter of the duplicate bug cannot get information, he, and the project contributors are forced to start side conversations. Is it possible to show some of the affects table from the master bug to answer some of the user’s questions? May I know the status and importance of the master bug? May I know the affected project if both bugs have the same affected project?

Conclusion

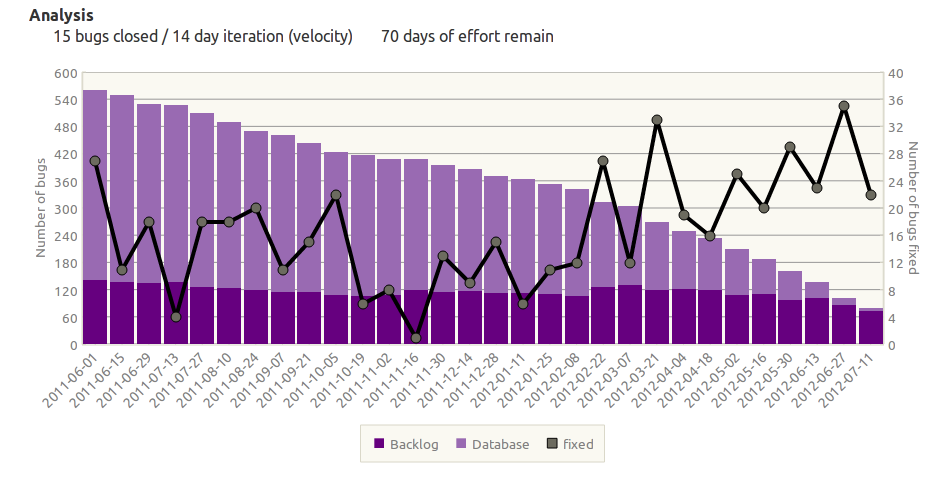

The Launchpad team will spend about 12 weeks creating the bug linking feature. The feature will emphasise the use cases needed to support two other features in development now, sharing and private projects. Proprietary data has less need for revising the bug affects table, though a unified presentation of linked bug and affects projects might need less effort to create.

The essential points about bug linking is that project needs to manage bug conversations to mange the disclosure of private information. Organisations split work into multiple bugs to mange conversations and organise work between different people. Launchpad could show and summarise the linked bugs so that contributors do not need to switch context to plan work.