A tale of two travesties

Published by Curtis Hovey April 16, 2012 in General

I have been looking for an easy and reliable way to develop and test Launchpad with Internet Explorer. Neither of the two common approaches used by Ubuntu users allows a Launchpad developer to easily verify that a change works with Internet Explorer. The challenge is to install a working version of Internet Explorer 8 and browse the local development instance of Launchpad. Maybe you can help me find a way to do this?

While Internet Explorer only represents 4% of Launchpad users, recent changes to make Launchpad easier to use made many tasks for IE users impossible to complete. This was unintended. It is a regression, and we treat all regressions as critical issues. The Purple squad reviewed the code and found that a lot of Launchpad JavaScript is disabled for all versions of Internet Explorer without an explanation nor fall-back behaviour. There is no documented way to ensure Launchpad works with Internet Explore, so most developers do not try to make it work.

Microsoft’s developer image of Windows 7 + IE8

Microsoft provides many images of Windows and IE so that Web developers can ensure their code works. The images are compatible with VirtualBox. The installation of the required software is easy, though configuration is tricky. The greatest challenge is creating a reusable Apache2 config for the many Launchpad domains.

Microsoft provides VPC compatible IE images to anyone who wants to verify that a website works with a specific version of IE. You will need about 13GB of disk space to install and run this bloatware that we all have come to expect with Windows. I installed the needed software using these commands:

$ cd /path/to/lots/of/disk/space/VirtualBox/HardDrives

$ sudo apt-get install virtualbox unrar curl

$ curl -L -O "http://download.microsoft.com/download/B/7/2/B72085AE-0F04-4C6F-9182-BF1EE90F5273/Windows_7_IE8.part0{1.exe,2.rar,3.rar,4.rar}"

$ unrar e Windows_7_IE8.part01.exe

I started VirtualBox and changed the preferences to use the path where I had lots of disk space. I created a new Windows 7 instance using the virtual disk. The disk had to be mounted as IDE (SATA failed) and the network was set as bridged.

IE worked perfectly with Ubuntu’s SSO. I could use Launchpad as I expected. In the cases where I expected a problem, I could see behaviours that confirmed my suspicion about the nature of the defect. This setup is ideal for verifying changes on Launchpad’s qastaging and production servers.

Making this setup work with the Launchpad development instance was very difficult. I hard-coded IP addresses to ensure that Windows and Apache knew the *.launchpad.dev sites. My IP address on my local network was 192.168.1.7 at that moment.

- Windows: Added

c:\windows\system32\drivers\etc\hosts

which contained

192.168.1.7 testopenid.dev launchpad.dev code.launchpad.dev answers.launchpad.dev blueprints.launchpad.dev bugs.launchpad.dev translations.launchpad.dev - Ubuntu: Copied

/etc/apache2/ssl/launchpad.crt

to a device that I could mount in Windows [1] - Windows: Added the launchpad SSL certificate to the Trusted root certificate store

Internet Options → Content → Certificates → Trusted Root Certification Authorities - Ubuntu: Updated all references in

/etc/apache2/sites-enabled/local-launchpad

of

127.0.0.88

to

192.168.1.7 - Ubuntu: Added

Allow from 192.168.1.*

after all occurrences of

Allow from localhost 127.0.0.0/255.0.0.0

I could login but I discovered that I occasionally needed to rearrange the entries in the Windows hosts file because it has a character limit! Every time my computer’s IP address changes, I need to update the Windows hosts file and the Ubuntu Apache config. I do not mind editing my IP in the Windows host file, but I do not like editing the entries or updating the Apache config. I doubt this setup works for developers using LXCs or other VMs to run Launchpad. I am planning to switch to LXC when Precise is released so this solution may not work for me in a few weeks.

Wine + Winetricks + IE8

Winetricks is a tool that can install and configure IE8 so that it runs on Ubuntu. Installation is very easy, but the UI’s controls and menus are broken. The greatest challenge is that the security behaviour is different from real Windows and IE — the browser thinks real Ubuntu SSO and the entire Launchpad development site is insecure so does not send the required REFERER header.

I installed the needed software using these commands:

$ sudo apt-get install wine winetricks

$ winetricks corefonts ie8

Configure Wine to work with launchpad development instance:

- Add the Launchpad SSL certificate to Wine [1]

$ wine control

Internet Settings → Content → Certificates → Trusted Root Certification Authorities - Run IE

$ wine iexplore

The UI does not look like IE8, and the broken buttons and menus certainly do not lend any confidence that this works. I can see from the Apache log that my request to https://launchpad.dev/claims to be MSIE 8. I cannot login to the website though. I can see in the logs that the REFERER header was not sent, so the post was rejected. The same is true for posting to the real Ubuntu SSO and Launchpad website — all posted forms fail. IE does this when it believes the browser is posting across a security boundary; it is protecting the user. Since the real Windows 7 + IE8 does not see either the development or production instance as unsecure, I know that something is misconfigured in Wine. I believe the SSL was install correctly because the real IE8 accepted it as did my Ubuntu browsers.

I can make the Launchpad development instance work with the broken Wine IE8 by hacking lp.services.webapp.publication to not requiring the REFERER header for MSIE 8 when the launchpad instance’s host end with “.dev”. This permits me to verify that JavaScript works, but is it really verifying that real IE8 works? I have no confidence in this hack. What else is broken in the setup?

[1] The default Launchpad SSL certificate in the Launchpad tree that is installed by rocketfuel-setup is incomplete. I generated a certificate that properly specified the sites it was for. I installed the better certificate in /etc/apache2/ssl and in my local OpenSSL store. The immediate benefit is that all of my development browsers accept the SSL certificate; not warning about wrong domains. I will add the better certificate to the Launchpad development tree and the script I used to generate and install it.

An introduction to our new sharing feature

Published by Curtis Hovey April 13, 2012 in Coming changes, Cool new stuff, Projects

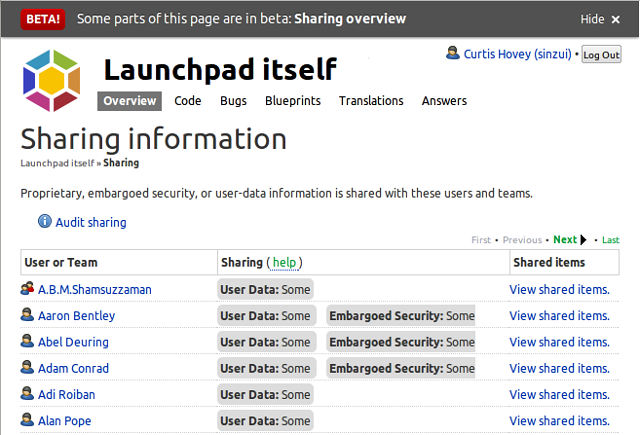

Launchpad can now show you all the people that your project is sharing private bugs and branches with. This new sharing feature is a few weeks away from being in beta, but the UI is informative, so we’re enabling this feature for members of the Launchpad Beta Testers team now. If you’d like to join, click on the ‘join’ link on the team page.

What you’ll see

Project maintainers and drivers can see all the users that are subscribed to private bugs and branches. The listing might be surprising, maybe even daunting. You may see people who no longer contribute to the project, or people you do not know at all. The listing of users and teams illustrates why we are creating a new way of sharing project information without managing bug and branch subscriptions.

If you’re a member of (or once you’re a member of, if we want people to join) the Launchpad Beta Testers team, you can find the Sharing link on the front page of your project. I cannot see who your project is sharing with, nor can you see who my projects are sharing with, but I will use the Launchpad project as an example to explain what the Launchpad team is seeing.

The Launchpad project

The Launchpad project is sharing private bugs and branches with 250 users and teams. This is the first time Launchpad has ever provided this information. It was impossible to audit a project to ensure confidential information is not disclosed to untrusted parties. I still do not know how many private bugs and branches the Launchpad project has, nor do I even know how many of these are shared with me. Maybe Launchpad will provide this information in the future.

Former developers still have access

I see about 30 former Launchpad and Canonical developers still have access to private bugs and branches. I do not think we should be sharing this information with them. I’m pretty sure they do not want to notified about these bugs and branches either. I suspect Launchpad is wasting bandwidth by sending emails to dead addresses.

Unknown users

I see about 100 users that I do not know. I believe they reported bugs that were marked private. Some may have been subscribed by users who were already subscribed to the bug. I can investigate the users and see the specific bug and branches that are shared with them.

The majority

The majority of users and teams that the Launchpad project is sharing with are members of either the Launchpad team or the Canonical team. I am not interested in investigating these people. I do not want to be managing their individual bug and branch subscriptions to ensure they have access to the information that they need to do their jobs. Soon I won’t have to think about this issue, nor will I see them listed on this page.

Next steps — sharing ‘All information’

In a few weeks I will share the Launchpad project’s private information with both the Launchpad team and the Canonical team. It takes seconds to do, and about 130 rows of listed users will be replaced with just two rows stating that ‘All information’ is shared with the Launchpad and Canonical teams. I will then stop sharing private information with all the former Launchpad and Canonical employees.

Looking into access via bug and branch subscriptions

Then I will investigate the users who have exceptional access via bug and branch subscriptions. I may stop sharing information with half of them because either they do not need to know about it, or the information should be public.

Bugs and private bugs

I could start investigating which bugs are shared with users now, but I happen to know that there are 29 bugs that the Launchpad team cannot see because they are not subscribed to the private bug. There are hundreds of private bugs in Launchpad that cannot be fixed because the people who can fix them were never subscribed. This will be moot once all private information in the Launchpad project is shared with the Launchpad team.

Unsubscribing users from bugs

Launchpad does not currently let me unsubscribe users from bugs. When project maintainers discover confidential information is disclosed to untrusted users, they ask the Launchpad Admins to unsubscribe the user. There are not enough hours in the day to for the Admins to do this. Just as Launchpad will let me share all information with a team or user, I will also be able to stop sharing.

(Image by loop_oh on flickr, creative commons license)

That Juju that you do (Part II: A magical balm to sooth your ills)

Published by Graham Binns April 3, 2012 in General

In my previous post I talked about the pain of having to set up a testing environment for our parallelised test work, and how there were an awful lot of hoops to jump through in order to get something usable up and running. Now, dear reader, let me tell you a tale of strangeness and charms.

Enter Juju

If you’re not familiar with Juju, I’d urge you to pay a visit to the Juju website to learn more, but in brief, I’ll explain: Juju is an orchestration service for Ubuntu. Using Juju allows you to deploy services rapidly, scaling up or down as you need. Each service is contained within a Charm, which is at it simplest a set of scripts that ensure that a given Juju unit does what it’s supposed to do at the appointed time (for example: install and config_changed are two of the most common hook scripts for a charm to have). We realised that in order to make our life simpler when testing our parallelisation work we could develop a pair of Buildbot Charms (one for the master, one for the slave) which when deployed through Juju, and given the right set of configuration options, would give us a working Buildbot setup on which to test Launchpad.

More about the charms…

The charms need to be able to automatically configure themselves to talk to each other (this is usually managed in Buildbot by static configuration files). Luckily, Juju provides for exactly that situation with the notion of “relations”; one charm can declare that it provides a particular interface as part of a relation and another can say that it requires that interface in order to be able to be a part of that relation. For our Buildbot charms, we have the following in the master’s metadata.yaml:

provides:

buildbot:

interface: master

And in the slave:

provides:

buildbot:

interface: slave

requires:

buildbot:

interface: master

Each charm has a couple of hooks that deal with relation, named in the form buildbot-relation-* where * is joined, changed or broken. These are run by Juju at the appropriate point in the process of connecting one instance to another. With all this in place, then, we can set up a working Buildbot environment by doing something like this:

$ juju bootstrap # create the Juju environment $ juju deploy buildbot-master —config=/path/to/master/config.yaml # deploy the master charm $ juju deploy buildbot-slave —config=/path/to/slave/config.yaml # deploy the slave charm $ juju add-relation buildbot-slave buildbot-master

The last line – juju add-relation buildbot-slave buildbot-master– tells Juju to connect the buildbot slave node to the master node. The two then do a bit of a dance to configure each other properly (in fact, it’s mostly a case of the slave saying: “Hey, I’m here, what do you want me to do?” and the master passing back configuration instructions). Once this is all done, you have a working Buildbot master and slave, ready to accept work to build.

What have we discovered about Juju?

First and foremost, we’ve learned just how powerful Juju actually is. We’ve taken a fairly complex-to-configure build environment, for which we normally use dedicated machinery whose configuration is not to be touched without sysadmin blessing on pain of pain, and turned it into something that we can deploy with four or five commands and a couple of configuration files. Sure, Juju has its quirks and oddnesses, but when we’ve run across them the Juju development team has been amazingly helpful with workarounds or, more usually, bug fixes. The current version of Juju is implemented in Python, too, so we find it pretty easy to contribute fixes of our own if we need to.

Where can I find out more?

As I said above, if you want to know more about Juju, you can check out the Juju website. If you want to take a look at our Buildbot charms and how we’ve built our hooks (they’re written in Python because that happens to be our language of choice, but in fact they can be written in anything so long as they’re executable), you can grab our code from Launchpad:

- For the master:

bzr branch lp:~yellow/charms/oneiric/buildbot-master/trunk buildbot-master - For the slave:

bzr branch lp:~yellow/charms/oneiric/buildbot-slave/trunk buildbot-slave

If you’ve got questions about Juju in general, the folks in #juju on Freenode are always tremendously helpful. If you’ve got any questions about our charms, ask them in the comments here and I’ll do my best to answer them.

((Image by http://www.samcatchesides.com/ under a Creative Commons license)

That Juju that you do (Part I: Bring the pain)

Published by Graham Binns March 30, 2012 in General

Benji’s blog post earlier this week gave you all some insight into what the Launchpad Yellow Squad has been doing recently in its attempt to parallelise the Launchpad test suite. One of the side effects of this is that we’ve been making quite a lot of use of Juju, and we thought it’d be nice to actually spell out what we’ve been doing.

The problem

We’re working to parallelise Launchpad’s test suite so that it doesn’t take approximately one epoch to get a branch from being approved for merging until it lands. A lofty goal, sure, and one that presents some interesting problems from the perspective of building an environment to test our work in. You see, Launchpad’s build infrastructure is a pretty complicated beast. It’s come a long way since the time when submitting a branch for merging meant sending an email to our PQM bot, which would then run the test suite and kick the branch out if it failed, but now it’s something of a behemoth.

Time for some S&M

We use Buildbot as our continuous integration system. There are two parts to Buildbot: the master and the slave. Broadly put, the slave is the part of Buildbot that is responsible for doing the actual work of compilation and running tests and the master is responsible for telling the slave when to do things. Each master can be responsible for several slaves. When it became obvious that we were going to need to essentially replicate our existing setup in order to test our parallelisation work, we considered asking Canonicals system administrators, in our sweetest tones, to give us a box upon which to do our testing work, but we spotted two reasons that this would be problematic:

- We didn’t actually know at the outset what the best architecture was for our project.

- Asking for a machine without knowing what you actually need is likely to earn you a look so old it could have come from an ammonite, at least if you have sensible sysadmins.

So instead, the obvious solution: use Amazon EC2. After all, that would allow us to play with different architectures without there being any huge cost in terms of physical resources. Moreover, we’d be able to have root access on the instances on which we were testing, which makes debugging such a complicated process so much easier.

However…

There was still a problem. How to actually set up the test instances, given that there are five of us spread between three timezones, that it takes a significant amount of time to set up a machine for Launchpad development, and finally that we don’t really want to leave EC2 instances running overnight if we don’t have to (because it’s expensive).

The sequence of steps we’d have to take to up an instance tends to look something like this:

- Launch a new EC2 instance (this happens pretty quickly, thanks, Amazon)

- Make sure that everyone’s public SSH keys are usable on that instance

- Run our Launchpad setup script(s) (this takes about an hour, usually).

- Install buildbot.

- Configure buildbot correctly as master or slave.

- Run buildbot (or buildslave, if this is a slave) and make sure it’s hooked up correctly to the other type of buildbot.

- Get some code into buildbot and make it run the test suite.

Parallelising the Unparallelisable

Published by Benji York March 27, 2012 in General

Launchpad has a lot of tests, almost 20,000. There are tests that make sure the internals work as expected, that verify the Javascript works in web browsers, and everything in between. In a perfect world those tests would only take seconds to run. In this world they take hours; six hours on our current continuous integration machines, for instance.

These long-running tests severely impact the time it takes to develop and deploy changes to Launchpad. We would like to improve the situation.

Given that the test cases are theoretically independent of one another, the obvious thing to do is to run the tests in parallel on a multi-core machine. Unfortunately many of the tests interact with the environment (databases, memcached, temporary directories, etc.) and conflict if run simultaneously.

Enter LXC

What we need is a way to isolate the test processes from each another. Virtual machines would allow us to do that, but the overhead and heavy-weight setup makes them unappealing. That’s where LXC (Linux Containers) comes in handy. LXC

allows the easy creation of “containers” that are isolated from the “host” machine without the performance overhead of VMs.

For example, to create a new container use lxc-create:

lxc-create -n test -t ubuntu

The container can then be started:

lxc-start -n test -d

And we can connect to it via SSH (using the default username and password shown during creation, if applicable):

ssh ubuntu@test

There are many options for customising the containers, including mounting a portion of the host’s file system in the container so sharing files between the two is easy.

Getting Ephemeral

All this is very nice for running isolated, parallel test runs but setting up and managing eight or more containers (one per core) is

off-putting, so we have used (and improved) a new LXC feature, “ephemeral” containers (created with lxc-start-ephemeral).

Ephemeral containers are “clones” of a base container and can have a temporary file system that reflects the contents of the base container but any writes are stored in-memory and are not written to disk. This allows us to install Launchpad on a single base container and then spawn many ephemeral containers, each with their own list of tests to run.

The ephemeral containers can then write to their local file systems without interfering with the others running simultaneously. The

containers may also benefit from faster IO because of the file system changes being stored in memory.

Results

We are still working out the kinks in our approach and wrestling with the occasional LXC bug as well as bugs in the Launchpad test suite itself. Even so we have already shortened a full test run on an eight-core EC2 instance down to 45 minutes; a substantial improvement over the current six hours.

(Image by Tolka Rova, Creative Commons license)

Why there is always time

Published by Dan Harrop-Griffiths March 21, 2012 in General

One of the main obstacles I come across when putting forward ideas for user testing for a project, is time:

“We’re on a very tight deadline, we can’t fit in testing,” “Can we leave it until the next release? There isn’t enough time at the moment.” “We just haven’t added in the time for all that user testing stuff.”

But the good news is – there is always time.

User testing, or usability testing (which is what we should really call it as we’re testing if things are usable, not testing the users themselves) can be extremely flexible. It can range from a detailed study of hundreds of painstakingly selected users, conducted in specially constructed labs with hidden screens, video recording devices and microphones, costing thousands of credits, with months to analyse and report the results. On the other end of the scale, it can simply be asking someone you pass in the corridor to look at a quick sketch of a wireframe you’ve made on the back of a napkin.

User testing can be both of these things, and everything in between, and yes, this can depend on time, and of course the other buzzword that sits so closely next to it – money. The thing is, it’s always better to do something, rather than nothing, however tight a deadline is – even if that is just asking a few users to try out a particular feature or function that you’re developing – whether this be with a flat mock-up or a working prototype.

Setting up some basic tests with a handful of users, running them and then writing up the results doesn’t need to take more than a day or two. The results will be pretty simple, and depending on the tests, will more likely be useful as a sense-check than a source of detailed information on user behaviour or working patterns, but this is still valuable stuff that can make or break a new feature. The results will broadly have one of three outcomes – user’s just didn’t ‘get it’ and there are big problems to be fixed; there are smaller problem’s that have slipped everyone’s mind but the user’s found fairly quickly; or (rarely, almost never) everything was perfect and the users had a seamless, faultless experience.

After I’ve reached this point in the discussion, I sometimes come across another potential user research blocker…

“But there’s no point in finding this out, we don’t have enough time to change things before our deadline.”

It may be true that there’s no time to redesign a feature based on recommendations from user testing results in your current cycle – but it’s better to go into the next phase of a project already knowing at least a bit about what user’s think. If you’re in the final stage of a project, these kind of problems can be treated as bugs and ticked off one at a time.

It’s easy to become blinkered with a project, working with the same concepts, terminology and use patterns day after day – it can become hard to think – “if I was looking at all this stuff for the first time, would it make sense?” User testing in its quickest and simplest form aims to answer this question. And that’s something there’s always time for.

Meet Laura Czajkowski

Published by Dan Harrop-Griffiths March 16, 2012 in General, Meet the devs

Dan: What’s your role on the Launchpad team?

Dan: What’s your role on the Launchpad team?

Laura: I’m the Launchpad Support Specialist, so my job is pretty varied each day. Launchpad is rather larger than I first ever thought or had experience in using but it’s great to see so many people use it on a daily basis.

My role is to help people via email or IRC with their queries or point them in the right direction of where they can get more information or submit a bug or help them achieve something. I also look after Launchpad bugs and questions each day and it’s fascinating to see the varying questions we get on there so it’s a great way to learn and also see what interesting projects are on Launchpad and the communities that use it.

Dan: You’ve been working on Launchpad as a community member for a while though yeah?

I’ve been using it in the Ubuntu community in the past for blueprints, reporting bugs and and tracking issues and the odd time if I can help out in translations.

Dan: What’s been the biggest challenge in your new role so far?

Laura: Bazaar and PPAs both of which are bizarre to me at present, but the folks in the Launchpad and Bazaar teams have been really helpful to me and really made working with them easy.

Dan: Where do you work, and what can you see from your window?

Laura: I live in London, and work from home four days a week so when I look out the window I see the reflection of the London Eye. The other day a week I head into Canonical HQ.

Dan: If time/money was not an issue, what would you change about Launchpad?

Laura: Oh I’d love to make Launchpad translatable as I do know many people who love to get more involved, having it translated would help here. I’d also love to get more of the developer community involved in Launchpad, and where Launchpad isn’t doing what they’d like get them to submit patches and get them more involved in the process. It’s open source after all 🙂

Dan: How did you first start to get involved in the open source community?

Laura:I got involved when I was in college where I was roped into joining our computer society Skynet. Soon I became treasurer and event organiser and then eventually president of the society and got involved running open source conferences. Never looked back since!

Work items in blueprints

Published by Matthew Revell March 15, 2012 in Cool new stuff

At its most basic, a blueprint in Launchpad is a statement of intent: by creating a blueprint, you’re saying, “Here’s an idea for how this project should progress.”

At its most basic, a blueprint in Launchpad is a statement of intent: by creating a blueprint, you’re saying, “Here’s an idea for how this project should progress.”

How do you track the detailed steps to get from having the idea to seeing it implemented?

The Ubuntu development community came up with a solution: they break a blueprint down into items of work that can be assigned to an individual. That makes it easier to track who’s doing what and how they’re getting on, while the blueprint itself tracks the status of the big idea.

Until now, these work items weren’t recognised by Launchpad. Instead, Ubuntu and Linaro tracked them in the blueprint’s whiteboard. Using the Launchpad API, they pulled the whiteboard contents out and used them to generate burn-down charts for status.ubuntu.com and status.linaro.org.

Now, thanks to work by some of the team at Linaro, each blueprint has a text box where you can add, update and delete its related work items.

How you make use of work items will depend on the project you’re working on. Both Ubuntu and Linaro already make extensive use of work items and, if you’re working as part of those communities, you should follow their lead.

Using work items

Work items are pretty simple to use.

Here’s an example of how a set of work items might look:

Design the user interaction: DONE

Visual design: INPROGRESS

Test the UI: TODO

Decide on an API format: POSTPONED

Bootstrap the dev environment: TODO

Set up Jenkins CI: TODO

As you can see, each work item sits on its own line and you indicate its status after a colon.

As you can see, each work item sits on its own line and you indicate its status after a colon. The statuses you can use are:

- TODO

- INPROGRESS

- POSTPONEDDONE

Sometimes a blueprint can be targeted to one milestone but you’ll have a individual work items that need to be targeted to a different milestone. That’s fine, you can tell Launchpad that a bunch of work items are for some other milestone.

In the work items text box, simply use a header like this:

Work items for <milestone>:

If you enter an invalid milestone you’ll get an error message and the opportunity to correct the text field.

A milestone picker will of course be more useful and we’ve submitted a bug to keep track of that.

What’s next?

Soon, you’ll be able get a view of all the work items and bugs assigned to a particular individual or team for a particular milestone.

Of course, if you have other ideas for how Launchpad can make use of work items, we’d love to hear from you.

Photo by Courtney Dirks. Licence: CC BY 2.0

Reimagining the nature of privacy in Launchpad (part 3)

Published by Curtis Hovey February 21, 2012 in Bug Tracking, Code, Coming changes

We are reimagining the nature of privacy in Launchpad. The goal of the disclosure feature is to introduce true private projects, and we are reconciling the contradictory implementations of privacy in bugs and branches.

Launchpad will use policies instead of roles to govern who has access to a kind of privacy

We are implementing three kinds of policies, proprietary, embargoed security, and user data. The maintainer is the default member of these policies. The maintainer can share a kind or private data by adding a user or team to a policy.

For proprietary projects, the maintainer can add their organisational teams to the proprietary policy to share all the project information with the team members.

For Ubuntu, the maintainer will set the apport bot to be the only user in the user data policy; user data is only shared with a bot that removes personal data so that the bug can be made public. The Ubuntu security team will be the only users in the security policy.

Most maintainers will want to add project drivers to the policies if they use drivers. Bug supervisors can be added as well, though the team must be exclusive (moderated or restricted).

You can still subscribe a user or team to a private bug or branch and Launchpad will also permit the user to access it without sharing everything with the user. The existing behaviour will continue to work but it will be an exception to the normal rules.

Polices replace the bug-subscription-on-privacy-change rules. If you have every had to change the bug supervisor for a project with many private bugs, you can rejoice. You will not need to manually update the subscriptions to the private bugs to do what Launchpad implied would happen. Subscriptions are just about notification. You will not be notified of proprietary changes is proprietary information is not shared with you. Sharing kinds or information via policy means that many existing private bugs without subscribers will finally be visible to project members who can fix the issue.

Reimagining the nature of privacy in Launchpad (part 2)

Published by Curtis Hovey February 15, 2012 in API, Bug Tracking, Code, Coming changes, General

We are reimagining the nature of privacy in Launchpad. The goal of the disclosure feature is to introduce true private projects, and we are reconciling the contradictory implementations of privacy in bugs and branches.

We are adding a new kind of privacy called “Proprietary” which will work differently than the current forms of privacy.

The information in proprietary data is not shared between projects. The conversations, client, customer, partner, company, and organisation data are held in confidence. proprietary information is unlikely to every be made public.

Many projects currently have private bugs and branches because they contain proprietary information. We expect to change these bugs from generic private to proprietary. We know that private bugs and branches that belong to projects that have only a proprietary license are intended to be proprietary. We will not change bugs that are public, described as security, or are shared with another project.

This point is a subtle change from what I have spoken and written previously. We are not changing the current forms of privacy. We do not assume that all private things are proprietary. We are adding a new kind of privacy that cannot be shared with other projects to ensure the information is not disclosed.

Launchpad currently permits projects to have default private bugs and branches. These features exist for proprietary projects. We will change the APIs to clarify this. eg:

project.private_bugs = True => project.default_proprietary_bugs = True

project.setBranchVisibilityTeamPolicy(FORBIDDEN) => project.default_proprietary_branches = True

Projects with commercial subscriptions will get the “proprietary” classification. Project contributors will be able to classify their bugs and branches as proprietary. The maintainers will be able to enable default proprietary bugs and branches.

Next part: Launchpad will use policies instead of roles to govern who has access to a kind of privacy.