Bug Linking Part 2

Published by Curtis Hovey June 13, 2012 in General

The Launchpad team is planning a new feature that will allow you to link bugs to each other and describe their relationship. The general idea is that you can say one bug depends of the fix of another. The goal is to make it clear where conversations to fix issues take place, who will do the work, and when the work can start.

I summarised the existing bug linking features and hacks previously. Now I want to explain the workflows and UI that Launchpad could support to create and explain relationships between bugs.

Managing bug relationships

Organisations and communities split issues into separate bugs when different people work at different times with different priorities to solve the bigger issue. Organisations and communities merge bugs when they want a single conversation to fix an issue that affects several projects at a single time. Explicit relationship between bugs (or the many projects listed on a single bug) would help projects organise work.

There are four general relationships that people try to describe when working to fix an issue. These relationship are either explicit, or implied when a bug affects multiple projects, or many bugs affect a single project. The relationship informs everyone about where the conversation to fix an issue happens, and the order of work to fix a group of issues.

- Duplicate: Bug X is the same as bug Y. The primary conversation about fixing the bug happens on bug Y. A secondary conversation happen on bug X. The affected projects, their status and importance, of bug X are identical to Bug Y.

- Dependency: Bug X depends on bug Y. Bug Y must be fixed before bug X can be fixed. The bugs have separate conversations, but each is informed of the other. Though the bugs have separate status and importance, there is some expectation that work proceeds from one bug to the next. As the bugs might affect different projects, the work to fix a bug may be done by different people. A project bug might depend on the fix in a library that is provided by another project. A bug in a distro series package might depend on the fix in an upstream project release. Dependency is implied when we see a bug that affects a distro package also affects the package’s upstream project.

- Similarity: Bug X and bug Y are caused by similar implementations. Bug X and Y require separate fixes that can happen concurrently. The bugs might share a conversation to find a fix, but the work and conversation is more often independent. In some cases, the proper fix is to create one implementation that the similar bugs depend on to fix the issue. A project might have two bugs caused by a bad pattern repeated in the code, or a pattern in one project is also used by another project. Each location of the pattern needs fixing. Maybe the right fix is to have a single implementation instead of multiple implementations.

- overlap: Fixing bug X changes the scope of work to fix bug Y. These bugs have separate conversations, but the work to fix each issue needs coordination. Fixing one bug may make the other invalid, or make it more difficult to fix the other. Maybe these bugs need to be redefined so that they do not overlap? Maybe bug X can be fixed at the same time as bug Y? Maybe both bugs really depend on an unknown root cause…bug Z?

We might imagine the relationships like sets. The duplicate bug is a subset of the master bug. Two bugs intersect in the overlap relationship. Similarity is a superset of several bugs. The dependency relationship has a direction pointing from one bug to the next.

Managing separate conversations

People working with proprietary information create duplicate and or dependent bugs to manage separate conversations. The “Affect project”, “Affects distro”, and “Duplicate” action do not work because they either mix conversations, or loose status and importance. Users benefit when private conversations are split from public ones, but Launchpad does not help the user do this.

Launchpad will not permit projects to share the forthcoming “proprietary” bug information type. Proprietary information is given to one project in confidence; The project cannot share that information with another project. The “Affects project”, “Affects distro” cannot add projects to the bug, so Launchpad must help users report a separate bugs.

When someone realises a private bug affects more than one project, Launchpad could help the user split the bug into separate bug reports to manage conversations and the order of work to fix the greater issue. Instead of adding a project or distro to the bug, the user might want to choose the project to report the bug in, and be prompted to revise the bug summary and description so that private information is not disclosed. The new bug is commonly public. It is the master bug, this is where the public conversation happens. This practice benefits more than the user who reported the bug…there is a public place for all users to discuss the issue.

Users are less likely to report a duplicate bug when Launchpad can show the public bug in the list of similar bugs. The principal cause of bug 434733 is not commercial projects, bug non-commercial projects like Ubuntu that mark bugs as duplicates of private bugs without consideration that users want to be informed and participate in the conversation.

Duplicate bugs continue to have separate side conversations that often focus on release issues. The discussion of how to fix the issue happens on the master bug. Duplicate bugs also have wasteful conversations that can be answered by the master bug. There is always a risk of disclosure when the reporter of a private bug has to visit the public bug to learn information that is pertinent to the private bug. The risk and inconvenience could be avoided by showing the important information on the duplicate bug — do not force users to change the context when working with private data.

We can substitute another relationship for “duplicate” in my case for separating discussions. When a fix for a bug is dependent on a one or more other bug fixes, there are several conversations with different people with different concerns. The same is true for bugs with similar or overlapping concerns. The only time conversations really need to be shared is to coordinate the timing or scope of the fixes.

While privacy is a primary reason to split conversations, splitting public conversations can benefit as well. The current UI that encourages a single conversation of ambiguously related downstream and upstream projects is a source of unwanted email. If I am only interested in the issues that affect my projects, do not make be get email for all the other projects. Splitting conversations into several bugs within a project is also a legitimate means to solve large problems that require different developers to fix code at different times. Minimising the notifications to just the relevant information keeps users focused on the issues.

Linking existing bugs

The workflow to select and link bugs is untrusted. When marking a bug as a duplicate, or linking a bug to a branch, Launchpad asks me to provide the bug number (Launchpad Id), then the page updates and I learn the consequences. Did I type the right number? Did people get emails about irrelevant or confidential information?

I expect Launchpad to ask me to review the bug I am linking and ask me to continue or cancel. Launchpad has to show enough information to answer my question’s and gain my trust:

- What is the bug’s summary?

- What is bug’s information type — is it private?

- Which projects does the bug affect?

- What are the bug’s tags?

- What is the bug’s description?

The presentation for bug listings provides most of this information. Launchpad could reuse the presentation (that I am already familiar with) when asking me to review the bug that matched the number I entered.

I imagine that if the action I am taking is specific, like marking a bug as a duplicate of another, Launchpad does not need to ask me about the relationship. In cases where the relationship is not implicit in the action, Launchpad must let me select the relationship between the bugs.

I know many users expect bug linking to work like selecting a user. They want to enter search criteria to see a listing of matches. The user might expand a match to see additional information. The user can select the bug, and maybe select the relationship to create the link. I am sceptical that this workflow would meet my needs. I often use advanced bug search to locate a bug; I cannot imagine offering advanced bug search in the small space to select a bug to link. The picker infrastructure that provides the workflows to select users and projects supports filters, which could be adapted to work with bug tags. I doubt this will be very useful. Advanced bug search does not work well across multiple projects, and bug linking does and must work across projects. I think people will still needs to use advanced search to locate the bug that they want to link.

Presenting a summary of the bug relationships

When an issue is represented by several bugs, or a bug affects several projects, users need known how they relate to understand where and when someone needs to take action. Users often open many pages because Launchpad cannot summarise the relationships between several bugs. Users will also read through long comments to learn why a bug affects many projects.

When viewing a bug, the user needs to see a listing of related bugs (dependency, similarity, and overlap). The listing summarises the affected project, status, importance, assignee, and milestone. Users might need to see bug tags, and badges for branches and patches. Maybe this is like the listing of bugs shown in bug search.

The affects table is a special bug listing. Does it need to be special? Users want to see the relationship between the items in the affects table. I want to know if the fix in a package depends on the fix in an upstream project. I am unsure how this could be done since there might be many relationships in the table. Maybe the many relationships, 3 or more affected project, packages, and series, will diminish when bug linking is available. We know that users unsubscribe when a bug affects many things because the conversation looses focus. When users can link bugs, there will be less needs to say a bug affects many things.

Privacy is a special case. A user can only see the relationship between two bugs if the user can see both bugs. When the listing contains private bugs, the presentation must call-out that they are seeing privileged information. Launchpad does not have a consistent way to show that part of a page contains private information.

- The user profile page will show locks before email addresses.

- Bug listings show a lock icon among other icons after the bug.

- Branch listings and linked branches show the lock icon after the branch.

Launchpad must make it clear to the user to not discuss the private relationships in the bug’s conversation.

Duplicates are presented differently from other bugs because they are subordinate to the master bug. There are several problems with the current presentation of duplicate bugs.

- Duplicate bugs show contradictory information in the affects table

- Duplicate bugs may not show the master bug if it is private

- Master bugs may show hundreds of duplicate bug numbers without summary or privacy information

- Why do I need to see all the duplicate bug numbers on a master bug?

Users do not need to see a list of all the duplicate bugs on the master bug. The number of duplicates is more interesting that a listing of numbers. User care about the duplicates they reported because they might want a side conversation, maybe Launchpad should show the user a link to the bug he or she reported? A contributor might want to read the the conversations in the duplicates for new information, so Launchpad does need to show a list of duplicates when the user asks for it. The listing of duplicates must indicate which are private. Other data like status and importance are irrelevant because the master bug provides the this information.

When I view a duplicate bug page, Launchpad must make it clear that this bug is a duplicate. I need to see the master bug’s information: affected project, importance, status, milestone, and assignee. I am not sure if the user should see its own affects table; that information would only be important if the bug was unduplicated.

There is a problem if the master bug is private and the user does not have permission to see the master bug. The user cannot see the master bug exists. Launchpad could prevent duplicate master bugs from being private if the project can have public bugs. In the case of projects with default proprietary bugs, the master bug will always be private. When the reporter of the duplicate bug cannot get information, he, and the project contributors are forced to start side conversations. Is it possible to show some of the affects table from the master bug to answer some of the user’s questions? May I know the status and importance of the master bug? May I know the affected project if both bugs have the same affected project?

Conclusion

The Launchpad team will spend about 12 weeks creating the bug linking feature. The feature will emphasise the use cases needed to support two other features in development now, sharing and private projects. Proprietary data has less need for revising the bug affects table, though a unified presentation of linked bug and affects projects might need less effort to create.

The essential points about bug linking is that project needs to manage bug conversations to mange the disclosure of private information. Organisations split work into multiple bugs to mange conversations and organise work between different people. Launchpad could show and summarise the linked bugs so that contributors do not need to switch context to plan work.

Launchpad for textual, graphical, and interactive browsers

Published by Curtis Hovey June 5, 2012 in General

I think Launchpad is missing fundamental HTML, CSS, and JavaScript to support the three classes of browser with which someone might visit Launchpad. There are inconsistencies in pages you might visit, and some parts might not work because Launchpad does not have a “proven way” to solve a problem. I am most concerned about the rules of when something should be shown or hidden.

I think Launchpad is missing fundamental HTML, CSS, and JavaScript to support the three classes of browser with which someone might visit Launchpad. There are inconsistencies in pages you might visit, and some parts might not work because Launchpad does not have a “proven way” to solve a problem. I am most concerned about the rules of when something should be shown or hidden.

Launchpad intends to look good in graphical browsers, and gracefully degrade for textual browsers. Launchpad intends to be usable by everyone, and interactive browsers get enhanced features that makes the site easier to work with. We expect everyone who works with Launchpad regularly to use an interactive browser which provides information as needed and the best performance to complete a task. Essential tasks must be performable by textual browsers.

The three classes of browser Launchpad developers need to design for

Textual browsers convey all information with text, layout is less important and graphics are irrelevant. Textual browsers might be text-based browsers like W3m or Lynx, or it might be a screen-reader like Orca with a graphical browser. Textual browsers can also be bots, or even the test browser used by Launchpad’s test suite. All essential information must be expressible as text.

Graphical browsers use CSS-based engines to layout text and graphics in two dimensions. Chromium and Firefox are two of many browsers that might be used. Launchpad wants to use CSS 3, but it cannot be required since some browsers like Internet Explorer 8 use CSS 2. There is also the concern that all browsers have CSS and HTML bugs that require some care when crafting a page.

Interactive browsers support JavaScript to change the page content based on user actions. Again, Chromium and Firefox are two of many browsers that might be used, but a minority of users choose to use platform browsers like Internet Explorer, Safari, or Konqueror. Launchpad wants to use EcmaScript level 5, but will accept ES 3 with proper design.

Showing the essential, offering the optional, and hiding the unneeded

Consider the case for reporting a bug. This is an essential task everyone must be able to perform with the browser that they have available. Some steps in reporting a bug are optional, and might even be considered a distraction. Reporting a bug can take many minutes, but it can be made faster by showing or updating information at the moment of need.

Launchpad commonly makes links to add/report something like this:

<a class="sprite add" href="+action"></a>

The markup relies on CSS to show an icon in the background of the space allocated to the link. There is no text to convey the action is “Report a bug”. We have struggled to make this markup work in all browsers. I personally do not think this markup is legal. Anchors may be empty because they can have name attributes without href attributes. The HTML specification does not state an empty anchor with a href must be rendered. Older versions of webkit and khtml certainly do not render the sprite because there is no content to show. This markup is missing a description of what the link does.

Launchpad makes some links for its test browser that just happen to work brilliantly with textual browsers:

<a class="sprite add" href="+action"><span class="invisible-link">Report a bug</span></a>

Graphical browsers see an icon, and textual browsers see text. Well, this is not exactly true. Older webkit browsers do not show text or icon because there is no text to render. We use JavaScript to add an additional CSS class to the page so that a special CSS rules can add content before the hidden text to make the link visible. The “invisible-link” name is bad though, we do want the link visible, we just want a icon shown when the browser supports it. Like the previous example, graphical browsers still do not see a description of what the link does.

Launchpad commonly uses expanders to hide and show optional content. The blocks look something like this:

<div class="collapsible">Options

<div class="unseen">bug tags [ ]</div>

</div>

Textual browsers can read the hidden content; they can set bug tags. Interactive browsers see “Options” and can reveal the content to set bug tags. Graphical browsers (or a browser where JavaScript failed) just see “Options”, it is not possible to set bug tags. The “unseen” CSS class could have been added after the script executed in the interactive browser to ensure it was hidden only if the browser could reveal it.

There is a problem with this example:

<input id="update-page" class="unseen" type="submit" name="update-page" value="Update Page" />

<img id="updating-content" class="unseen" src="/@@/spinner" />

Launchpad does not have classes that distinguish between interactive content that is “unseen” and graphical content that is “unseen”. The first line means interactive browsers cannot see the input element, and the second line means graphical browsers cannot see the img element. This ambiguity leads to cases where content that should be seen is missing, or vice versa.

Launchpad needs classes that mean what we intend

- I image four classes are need to handle the cases for the three classes of browser.

- readable

- Textual browser can read or speak the content.

Graphical and interactive browsers to not show the content.

eg. links with sprites. - enhanceable

- Textual and Graphical browsers can read, speak, and see the content.

Interactive browsers do not show the content, but can reveal it.

eg. expanders that show additional information or optional fields. - replaceable

- Textual and Graphical browsers can read, speak, and see the content.

Interactive browsers do not see the content because it is superseded.

eg. forms that reload the page. - revealable

- Textual and graphical browsers cannot read, speak, or see the content.

Interactive browsers do not show the content, but can reveal it.

eg. spinners that show loading in-page content.

The CSS classes need to interact with other classes on the page that help identify the class of browser:

- readable

- May need aural CSS to ensure it can be read and spoken.

- enhanceable

- No special properties needed.

- enhanceable hidden

- Scripts add the hidden class at the end of a successful setup because the content can be shown.

- enhanceable shown

- Scripts add the shown class at the end of a successful setup because the content can be hidden.

- replaceable

- No special properties needed.

- replaceable hidden

- Scripts add the hidden class at the end of of a successful setup because the content was replaced by interactive content.

- revealable

- The is not displayed because the browser must prove it can interact with it.

- revealable shown

- Scripts add the shown class at the end of a successful setup because the browser has demonstrated it can interact with the content.

Both the single “enhanceable” and “revealable” could be omitted because they are redundant with “enhanceable shown” and “revealable hidden”. I think the habit of placing classes that hide and show content in the page templates is dangerous. There are lots of cases where the page assumes a state before the class of browser is known. Page templates that use either “unseen”, or the “hidden” class assume an interactive browser. It is not clear if textual and graphical browsers work by design, or by accident.

A story of a clinic

Published by Graham Binns June 1, 2012 in General

You’ll remember that a while back, dear reader, we announced that we’d be running a couple of Launchpad Development Clinics at UDS (we called them Launchpad Clinics at the time, and I lost count of how many people commented that that sounded as though Launchpad was ill. It isn’t; it’s in the same rude health that it always was). We’ll come up with a better name next year!

Anyway, we made the announcement, put up the wiki page, saw a few names and bugs added to it, and didn’t really expect to be hugely busy. Indeed, when Laura, Matthew, Huw, Raphaël and I convened in one of the UDS meeting rooms for the first clinic, it was mostly empty except for the stragglers from the previous session.

Then a person appeared. Actually, it was two people squeezed into the skin of one person: Tim Penhey, who looks like he’s been chiseled out of granite and has a tendency to loom well-meaningly, like an avuncular greek pillar. We figured that since he’s an ex-Launchpadder, he didn’t count, and so went back to self-deprecatory joking whilst worrying that we’d massively miscalculated how many people would want to come to the clinics.

And then another person arrived. And another, and another. Soon, we’d gone from having a couple of attendees who really just needed to run ideas past a Launchpad core developer to having ten people who all needed questions answered, or a development instance spun up. After that, things get a bit fuzzy, because I was always answering someone’s question or being root on an EC2 instance for someone else. When Laura told us that our time was up I was, I have to confess, somewhat surprised.

Thursday’s session was a quieter affair, in part at least because we had to reschedule it at the last minute (UDS schedules are like quicksand, and if it weren’t for the amazing UDS admin team everyone would be thoroughly lost for much of the time), but there were still people there with bugs to be fixed and questions to be answered. I had preliminary discussions with Chris Johnston about adding API support to Blueprints, and worked with Ursula Junque on working out how to add activity logging to the same.

The upshot of the clinics is, I think, massively positive. There is a genuine development community out there for Launchpad, and people really are keen to make changes to the dear old Beast whilst the Launchpad core developers are working elsewhere or fixing things that are horribly complex (and usually not user-facing). For someone like me, who had been somewhat skeptical about the kind of response the clinics would receive (even though they were partly my idea), this is immensely gratifying news.

There are, of course, many things that we need to improve on, and many lessons that we can learn. People want to know how to fix a simple bug without having to come to a session at UDS, so I’m going to record a screencast of just such a procedure, right from finding the bug to working out where the fix lives, all the way through the coding and testing process, right up to the point of getting the branch reviewed and landed. Hopefully this will give everyone a great jumping-off point.

When we set out on this particular journey, one of the criteria I wrote down for considering the clinics a success was “we’ll want to do it again at the next UDS.” Well, I do. We did well; we can and will do better next time. Who’s with me?

Bug Linking Part 1

Published by Curtis Hovey May 29, 2012 in General

The Launchpad team is planning a new feature that will allow you to link bugs to each other and describe their relationship. The general idea is that you can say one bug depends of the fix of another.

We’ll be asking you to help us decide the scope of this feature, so look out for invitations to user research sessions over the coming weeks if you’d like to get involved.

Key Issues

There are issues about the kinds of relationship that should be supported and the types of workflows to use them. Before I describe the workflows and relationships that we have discussed, I think I should first write about the existing bug linking features and hacks.

Affects Project or Package

Launchpad has always recognised that a bug can affect many projects and packages. Launchpad defines a bug as an issue that has a conversation. The information in the conversation is commonly public, but it might be private because it contains security, proprietary or personal information. An issue can affect one or more projects and packages, and each will track its own progress to close the bug.

A bug in a package often originates in the upstream project’s code. I assume that when I see a project and a package listed in the same bug that there is an upstream relationship, but that is not always the case. So some bugs affect multiple packages and projects? How do I interpret this? Maybe one project is a library used by other projects. Maybe the projects and packages cargo-cult broken code that require independent fixes. Maybe the code from one project is included in the source tree of other projects. When I look at the table of affected projects and packages on a bug, I have to guess how they relate. I don’t know if fixes happen in a sequence, or at the same time as each other. Is one project fixed automatically by a fix in another project?

Contributors from all the affected projects contribute to the conversation. The conversation can be hard to read when several projects are discussing their own solution. It is common for everyone from one project to unsubscribe from a bug when the project marks the bug as fixed. This is a case were users are still getting bug mail about an issue that is fixed for them. Maybe there’s more than one issue if there’s more than one conversation happening?

Duplicate

Users commonly report bugs that are duplicates of other bugs. Marking a bug a duplicate of another means that the conversation and progress about an issue is happening somewhere else.

It is common for duplicate bugs to affect different projects from the master bug. Was the duplicate wrong, or maybe Launchpad did not add the duplicate’s affected projects to the master bug’s affected projects?

I can mark your bug to be a duplicate of a bug that you can’t see (because it is private). This is very bad. If I do this, you cannot participate in the conversation to fix the bug, and you don’t know when the bug will be fixed. It is common practice to make the first reported occurrence of a bug the master of all the duplicates, but if the first occurrence has personal information in it, it probably cannot ever be public. Thoughtful users create public versions of bugs and make them the masters of the duplicates so that everyone can participate and be informed.

Links in Comments

Launchpad automatically links text that appears to be a bug number. A user can add a comment about another bug and any user can follow the link to see the bug.

There are many kinds of relationships described in comments which contain linked bugs: “B might be a duplicate of C”, “D must be fixed before E”, “F overlaps with G”, “H invalidates J”, “K is the same area of code as L”, “M is the master issue of N”. I cannot see the status of the linked bugs without opening the bug. Maybe the bug was marked invalid or fixed? Bug comments cannot be edited, so the links in the comments might be historic cruft.

Bug Tags

Bug tags allow projects to classify the themes described and implied in a bug. Projects can use many tags to state how a bug relates to a problem domain, a component, a subsystem, a feature, or an estimate of complexity. Launchpad does not impose an order upon bug tags.

Some projects repurpose/subvert bug tags to describe a relationship between two or more bugs. The tag might describe a relationship and master bug number, such as “dependent-on-123456” and a handful of bugs will use it. Multiple tags might be used on one bug to describe all the directions of the relationships. A search for the tag will show the related bugs and you can see their status, importances, and assignee. The tag becomes obsolete when all all its bugs are closed. There might be more obsolete bug tags then operational ones. Bug numbers embedded in the tags are not updated if one bug becomes the duplicate of another.

Bug Watches

Bug watches sync the status and comments of a bug in a remote bug tracker to Launchpad. Projects can state that the root cause of a problem is in another project, and that project uses another bug tracker. The bug watch is presented in the bug affects table as a separate row so that users can see the remote information with the Launchpad information.

When the bug watch reports the bug is fixed, the other projects can then prepare their fixes based on the watched project’s changes. Since the information is shown in the bug affects table, it has all the same relationship problems previously described. I do not know if I need to get the latest release from the watch project, or create patch, or do nothing. Launchpad interleaves the comments from the remote bug tracker with the Launchpad bug comments, which means there is more than one conversation happening. The UI does distinguish between the comments, but it is not always clear that there are two conversations in the UI and in email.

Next

Workflows that that use related bugs.

How bug information types work with privacy

Published by Curtis Hovey May 23, 2012 in General

Launchpad beta testers are seeing information types on bug reports. Launchpad replaced the private and security checkboxes with an information type chooser. The information types determine who may know about the bug.

When you report a bug, you can choose the information type that describes the bug’s content. The person who triages the bug may change the information type. Information types may also change as a part of a workflow, for example, a bug may start as Embargoed Security while the bug is being fixed, then the release manager can change the information type to Unembargoed Security after the release.

Testing in phases

In the first phase of this beta, Launchpad continues to share private information with bug supervisors and security contacts using bug subscriptions. The project maintainer may be managing hundreds of bug subscriptions to private bugs, and people are getting unwanted bug mail.

In the second phase of the beta, the project maintainer can share information types with people…the maintainer is only managing shares with a few teams and users and people are not getting unwanted bug mail.

Watch the video of information types and sharing to see the feature in use and hints of the future.

One in a million

Published by Dan Harrop-Griffiths May 16, 2012 in General

Today at some time around 3am UTC, the one millionth (1,000,000th) bug was filed in Launchpad:

https://bugs.launchpad.net/edubuntu/+bug/1000000 (congrats Stéphane Graber!)

This is a huge milestone for everyone that uses and contributes to Launchpad and serves as a great witness to all the achievements, trials and challenges we’ve faced over the past 7 years. Today’s post is made up of contributions from some of the people who’ve worked with Launchpad and on developing Launchpad itself, right from the very start, up until fairly recently, like myself.

We’d love to hear your thoughts and experiences too, so please add a comment at the end if you have a story to share.

Francis Lacoste – Launchpad Manager

“Launchpad is vast. The significant milestones reached could be quite varied. But to me, the most important ones are the ones that enabled a community to use Launchpad for new activities. Thus, the first milestone was in the very earliest days, when the Ubuntu community switched from Bugzilla to Launchpad for tracking Ubuntu bugs!

“Other important milestones were when bzr and Launchpad code hosting were fast enough to host the huge Launchpad source tree itself (back in 2007). Then in 2008, when Launchpad started using Launchpad for code reviews! Other significant milestones were when MySQL joined Launchpad and bzr also in 2008. This opened the door for other big communities to join Launchpad: drizzle and then OpenStack. Finally, more recent milestones of this sort were when we introduced source package branches and Ubuntu started importing all of their packages in bzr: https://code.launchpad.net/ubuntu

“Last year, we introduced derived distributions which is now being used to synchronize with Debian development versions.”

Matthew Revell – Launchpad Product Manager

“There’s so much in Launchpad that it’s almost impossible to settle on a particular highlight. However, PPAs stick out as something of a game-changer. Someone once said that the cool thing about apt isn’t so much apt, but actually the software archive behind it. I love that I can trust the Ubuntu archive to give me what I need in a reliable form.

“However, PPAs have helped bring greater diversity to Ubuntu by allowing anyone to build and publish their own packages in their own apt repository. With the addition of private PPAs and package branches, we have probably the best combination of centralised repos and software from elsewhere that I’ve seen in any operating system.”

Dave Walker (Daviey) – Engineering Manager, Ubuntu Server Infrastructure

“The real shining star is Launchpad bugs, the features and flexibility has really enabled the server team to deliver a quality product. It’s rich API allows ease of mashups, and easy task prioritisation.”

Graham Binns – Software Engineer, Launchpad

“Probably the most significant moment for me over the time I’ve worked on Launchpad was its open-sourcing. Suddenly, this big beast that we’d worked on for years was open to outside contributions, and that was and still is incredibly exciting to me.”

Laura Czajkowski – Launchpad Support Specialist

“I think the best thing I’ve seen in a long time on Launchpad was the set downtime and reduced downtime that happens each day. This minimises the effect for all projects hosted on launchpad an many people never even notice it down.”

J.C.Sackett – Software Engineer, Launchpad

“When I started on launchpad, the volume of bug data was a source of constant performance problems. Our 1 millionth bug is noteworthy in that we’re handling 1 million bugs better now than we were handling 500,000 then.”

Curtis Hovey – Launchpad Squad Lead

“Launchpad’s recipes rock. They allow projects to automatically publish packages created from the latest commits to their branch. Users can test the latest fixes and features hours after a developer commits the work.”

Diogo Matsubara – QA Engineer

“Personal package archives combined with source package recipes allows any Launchpad user to easily put their software into Ubuntu and this is a pretty unique feature from Launchpad.”

Tom Ellis – Premium Service Engineer

“It’s been great to see Launchpad grow and scale. A key milestone for me was seeing Launchpad move from a system that was not scaling well to one which has been a great example of continuous development and seeing the web UI improve in usability.”

(Photo by ‘bunchofpants’ on flickr, Creative Commons license)

Testing descriptions for bug status and importance

Published by Curtis Hovey May 8, 2012 in General

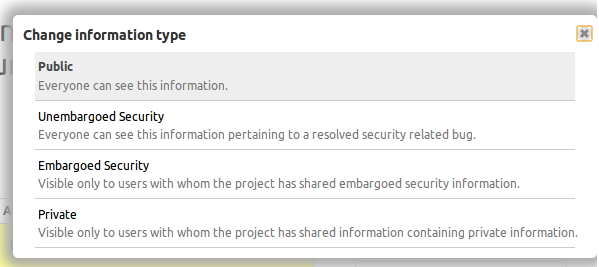

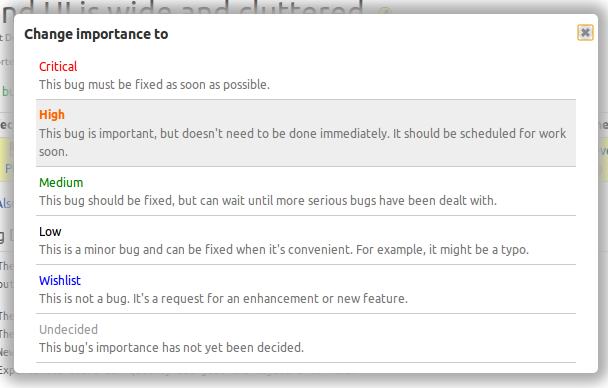

Launchpad beta testers will now see the descriptions of bug status and importance when making updates to the bug page. Launchpad pickers can now show the descriptions of the options you can choose.

Launchpad’s rules for defining a list of options you can choose have always required descriptions, but the only places you could see them were in some forms where they were listed as radio buttons. Bug status and importance where never shown as radio buttons, so their description were only know to people who read Launchpad’s source code. Users need to see the descriptions so that there is a common understanding of terms that allows us to collaborate. The original bug importance descriptions were written in 2006 and only made sense for Ubuntu bugs. We revised the descriptions for the improved picker.

There has been a lot of confusion and disagreement about the meaning of bug statuses. Since users could not see the descriptions, we posted the definition on help.launchpad.net. Separating the status description from the status title did not end the confusion. We revised the descriptions for the improved picker, but I think we need to make more changes before showing this to everyone. The picker appears to rely on colour to separate the choice title from description. Not all choices will have a special colour, and in the case of bug status there are two choices that appear to be the same grey as the description text:

The picker enhancements were made for the disclosure feature. We are changing the presentation of bug and branch privacy to work with the forthcoming project sharing enhancements. Early testing revealed that users need to know who will be permitted to see the private information when the bug is changed. This issue was similar to the long standing problem with bug status and importance. We decided to create a new picker that solved the old problem, that we could then reuse to solve the new problem.

Five kinds of branches

Published by Curtis Hovey May 7, 2012 in General

I do not like the Launchpad branch page. It is rarely informative and I would like to ignore it, but there are a few tasks that I can only perform form that page. I think the page could be better if it were possible for me to state the branches’s purpose.

I sat down the Huw, the Launchpad team’s designer to discuss the page almost two years. He was struggling to make sense of the the branch page from a developer’s perspective. At that time I concluded that I disliked the page because it treats all branches as if they have the same needs, which ignores the fact that every branch has a purpose. A branch’s purpose determines what I need to know and what actions I can take. I saw two purposes at the time, but I recently concluded in a sleepless state that there are five purposes. Maybe this was a delusion created by the fever. Let’s see if I still think that at the end of this post.

The branch page is missing:

- A statement of intent

What is the branch’s purpose? This determines the action I can perform and the information I need to see. Is this branch trunk, a supported series, for packaging, a feature, or a fix? - A record of content

I want to browse the files of some branches, while other branches I only care about the diff. - A testament of accomplishment

A branch’s purpose determines its goal. The goal of most branches is to merge with another branch. Some branched though must create releases or packages.

The features a branch needs are mostly determined by the how long the branch is expected to live:

- Short-lived branches

The branch is often based on trunk, its purpose is to fix or add a feature (Bug or blueprints), and it goal it is to merge into its base branch. - Long-lived branches

The branch is often the basis of other work. It is the sum of many merges, often summarised as milestones. The goal of the branch is to create releases.

Trunk branch

The most important branch to every project is the one designated to be trunk. This branch will live for months, or years. This is the branch I use as the basis for my changes. It is the goal of most derived branches to merge with this branch. The goal of trunk is to make releases.

There is no need to show me which bugs are fixed or blueprints (features) are implemented in trunk. Trunk is everything to the project. When we say there is a bug in a project, we really know that bug is in trunk. Launchpad could change how it models bugs to make this case clear. The bug tracker or specification tracker are the only tools that can adequately explain which bugs and blueprints were closed. I might be interested in which bugs and blueprints were recently fixed in trunk though.

The merge action does not make sense. It is the goal of other branches to merge with trunk…trunk does not merge with other branches! Well this is not entirely true in the packaging case, which I will explain shortly. I am interested is seeing the list of recently proposed merges into this branch. The branch log shows me which branches were merged.

I want Launchpad to shown me the bugs and blueprints that the project drivers plan to fix. Will my bugs be solved soon? Can I contribute? Launchpad actually can show me this on the series page. Launchpad separates the concept of planning changes (feature and fixes) from branch. There is good reason for this, but the separation of information creates a chasm that many developers fail to cross.

We commonly organise change into milestones, and each milestone may culminate in a release. A series of milestones represent continuity and compatibility. Distributions have a series without having a trunk branch. There are also projects that do not produce code, but have bugs and blueprints. Launchpad is also a registry of projects and releases that are packaged in Ubuntu.

Launchpad creates a trunk series for every registered project because we believe all projects should state their intent and distinguish between different bases of code. But where is the code? Where is my branch? I commonly see projects with series information without a branch, and I commonly see projects without series information, with tremendous branch activity. It is difficult to contribute when you cannot see what is happening and what needs to happen. Project maintainers are equally frustrated; Launchpad is not helping them to create releases from their trunk branch.

Launchpad asks me to link a branch to a series, but I think most developers want to state that their branch is the trunk series, or is a supported series. The branch is elevated to a new role and it gets the features that the role needs. I want one page about the trunk branch, not a page about planning and a page about branch metadata.

Supported series branch

A supported branch represents a previous project release. It is a historic version of trunk with its own bugs and features. Like trunk, the linked bugs and branches do not make sense, nor do I want to merge a supported branch into another branch. A supported branch can live for months or years. Some fixes (branches) will be merged into the support branch. Feature branches are never merged into supported branches.

In the case of a supported branch, I most want to know the milestones/releases that represent the life of support. I want to know which fixes in trunk will be backported to the supported branch. I might be interested in knowing the fixes (branches) that were recently merged.

Packaging release branch

A packaging branch contains additional files needed to create an installable package from a project’s release. A packaging branch often has counter-part branch, usually a supported branch, but sometimes trunk. Thus the packaging branch lives for months or years. The packaging branch may only contain the extra files to create a package using a nesting recipe, or it contains repeated merges of the counter-part branch. I am only interested is seeing the differences from the counter-part branch. I do not want to browse all files in the branch.

Packaging branches have their own set of bugs — the files introduce bugs and yet some of the patch files fix bugs in the counter-part branch. Thus we might image that the packaging branch is the sum of the bugs in the supported and packaging branch, minus the fixes provided by patches.

Packaging branches are often managed by different people from the project’s developers. Their skills and permissions are often different too. A patch to expediently fix a bug in the packaging branch might take much longer merge into the supporting branch where the bug originates.

Feature (blueprint) branch

A feature branch adds new functions to the code. It is short-lived, measured in days or weeks. The branch is based on trunk and is goal is to merge with trunk.

Feature branches need all the features that the current branch page provides. The feature branches has blueprints that specify what functions are being added and the criteria to know when the feature is done. They may also fix bugs. A recipe can be used to build an unstable package for testing.

Merges are far more complex for feature branches than is implied by the Launchpad’s UI. There are many workflows where a feature branch is actually composed of several branches that might be merged with trunk individually, or they are merged as a whole when the feature us deemed stable. Launchpad should encourage me to merge the branch into trunk, merging into another kind of branch doesn’t make sense. The UI does not properly show that I may merge my feature branch into trunk several times, or that several branches might merge into my feature branch.

I am only interested in seeing the changes from trunk. I do not want to browse all the files in the branch. Since a feature branch can be composed of many branches, I want to see the difference between the merges to understand the revision changes.

Fix (bug) branch

A Fix branch exists to close a bug. The branch is short lived, measure in hours or days. Its goal is to merge with its base branch. The older the branch gets, the more likely that it has failed.

It does not have related blueprints or recipes. I am not interest on seeing all the files and code in the branch; I only care about the changes from base.

A fix branch needs to tell me which bugs it fixes. It must encourage me to merge the fix back into the base branch.

Most fixes are based on trunk and will merge with trunk, but when a bug also affects a supported branch, Launchpad might want to encourage me to propose a backport. Launchpad currently allows me to nominate/target a bug to a series (which is ultimately a branch) when there is no fix. I think this is odd. Project development is focused on trunk, fixes are almost always made in trunk first. Once trunk has the fix, it is possible to determine the effort needed to backport it to a supported branch. If a bug is only in a supported branch, then I think it is fine for Launchpad to allow me to nominate it to be fixed, which implies the fix is already in trunk.

Conclusion

Hurray! I still think there are five kinds of branches which different needs. This issue is like a bad word processor which treats a letter, a report, and a novel the same. A good word processor knows the document’s intent and changes the UI and available features so that I can complete my task without distraction. The current branch page emphasizes what all branches have in common, but it needs to emphasise the differences so that I know what I need to do. There are no plans to change the branch UI, but contributors are welcome to improve Lp. I hope my thoughts will contribute to a proper analysis of features the branch page must support.

Launchpad Clinic at UDS-Q

Published by Laura czajkowski April 30, 2012 in Meet the devs

Let’s face it. Launchpad is not without its bugs. Everyone probably has at least one that they’d like to see fixed, and most of those that do also have the ability to fix them, if only they could get a leg-up on the learning curve of Launchpad development.

To that end, Graham Binns and I will be running two Launchpad Development Clinics at UDS-Q. We’ll be there to help you get on the road to getting your bugs fixed, and to offer advice on every step of the Launchpad development process. We’ll have EC2 instances ready for you to develop on, so if you haven’t already gone through the process of setting up local Launchpad development on your machine, you don’t need to worry.

I have created a wiki page on which you should register if you’re going to be attending either of the clinics. Just list your name and the ID of the bug(s) you want to work on on that page. We’ll check the bugs out and get in touch with you if we think they’re too big to work on in the clinics – in which case we’ll try and work with you to get them fixed over a longer period. We’ve added the event to summit schedule, for Tuesday and Thursday of UDS so why not sign up and come along!

I’m looking forward to hearing from you all, and to helping you make Launchpad awesome(r).

Contributing to Launchpad

Published by Laura czajkowski April 26, 2012 in General, Meet the devs

Ever wished there was just one feature you’d like to see enabled in Launchpad. Ever wondered when one of the bugs you have taken the time to report and document would be implemented. Well how about we help you to get these bugs fixed. Launchpad is a free and open source project, its platform is also open and developed in a transparent fashion. The source code for every feature, change and enhancement can be obtained and reviewed.

This means you can actively get involved in improving it and the community of Ubuntu platform developers is always interested in helping peers getting started. The Launchpad development team are continuously working on areas in Launchpad and other projects but there just isn’t enough time in the day to get every bug fixed, tested, deployed and out there. What we’d like to help to do is encourage and help users get more involved. We would like to get more of the developer community involved in Launchpad, users who’ve never developed before to experienced hands on developers and show you how to get started. There is documentation written up, but we’re going to explain it a less scary way in basic steps.

Getting Started

First things first, you need bzr. All of Launchpad’s branches use bzr for source control, so you’ll need to install it using apt-get:

$ apt-get install bzr

Next, you need to create a space in which to do your development work. We’ll call it ~/launchpad, but you can put it pretty much anywhere you like on your system.

$ mkdir ~/launchpad

Because getting all the ducks in a row to make it possible to do Launchpad work takes a while, we’ve actually got a script that does all the legwork for you. It’s called rocketfuel-setup (see what we did there?) and once you’ve got bzr installed, you can

$ cd ~/launchpad $ bzr --no-plugins cat http://bazaar.launchpad.net/~launchpad-pqm/launchpad/devel/utilities/rocketfuel-setup > rocketfuel-setup $ chmod a+x rocketfuel-setup $ ./rocketfuel-setup

You’ll be prompted for various details, such as your Launchpad username, and you’ll be asked for your password so that rocketfuel-setup can install all the packages that Launchpad needs. After this, you might as well go and have a sandwich, because downloading and building the source code will take at least 40 minutes on a first run.

Once rocketfuel-setup has completed on your machine, your ~launchpad directory will look something like this:

$ ls ~/launchpad/ lp-branches lp-sourcedeps rocketfuel-setup

The only directory you need to worry about in there for now is lp-branches. As the name suggests, this is where your Launchpad branches are stored.

Now that you’re all set up, it’s time to find a bug to fix and get some coding done!

Where to Begin

Now, it’s fair to say that there are plenty of bugs in Launchpad worth fixing. However, it’s even fairer to say that you don’t want to pick on of the Critical bugs as your first effort for Launchpad development, mostly because the Critical bugs are all fairly complex.

Luckily, the Launchpad team maintains a list of trivial bugs – the ones with simple, one-or-two line fixes that we just haven’t been able to get around to yet. You can find it here on Launchpad.

Once you’ve found a bug you want to fix, you need to create a branch for it. There are some utility scripts to make your life a bit easier here. In this case, rocketfuel-branch, which creates a new Launchpad branch from the devel branch that rocketfuel-setup created.

$ rocketfuel-branch my-branch-for-bug-12345

You’ll now find that branch in ~launchpad/lp-branches

$ ls ~/launchpad/lp-branches devel my-branch-for-bug-12345 $ cd ~/launchpad/lp-branches/my-branch-for-bug-12345

Now that you’ve got a branch to work in, you can start hacking! Before you do, though, you should talk to someone in #launchpad-dev on Freenode about the problem you’re trying to solve. They will help you figure out how best to solve the problem and how best to write tests for your solution. We call this the “pre-implementation call” (though it can happen on IRC) and it’s very important, especially for first time contributors.

Once you’ve had your pre-imp call, you can get coding. Don’t forget that the people in #launchpad-dev are there to help you as you go. Don’t worry if you get stuck; Launchpad is a very large project and even seasoned developers get lost in the undergrowth from time to time. Thankfully, there’s a team of committed people who are able to wade in with machetes and rescue them. I’m going to stop this analogy now, since it’s starting to wither.

What to do once you’re written code

Once you’ve finished hacking on your branch, you need to get it reviewed. Launchpad has a feature that makes this really, really simple, called Merge Proposals. Here’s how it works.

First, commit your changes to your branch (you should have been doing this all along anyway, but just in case…) and push them to Launchpad:

$ bzr ci -m "Here are some changes that I made earlier, with a useful commit message." $ bzr push Using saved push location: lp:~yourname/launchpad/my-branch-for-bug-12345 Using default stacking branch /+branch-id/24637 at chroot-83246544:///~yourname/launchpad/ Created new stacked branch referring to /+branch-id/24637.

You can now view the branch on Launchpad by using the bzr lp-open command:

$ bzr lp-open Opening https://code.launchpad.net/~yourname/launchpad/my-branch-for-bug-12345 in web browser

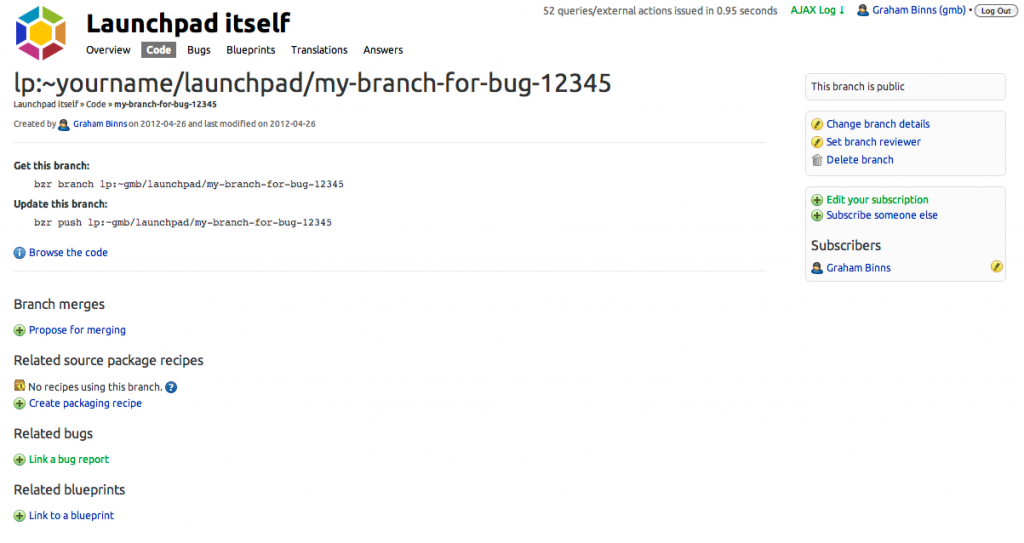

The page that will open in your browser contains a summary of the branch you’ve pushed, and will look something like this:

You can link it to the bug you’re fixing by clicking “Link a bug report”. If you’ve named your branch something like “foo-bug-12345”, Launchpad will guess that you want to link it to bug 12345 in order to save you some time.

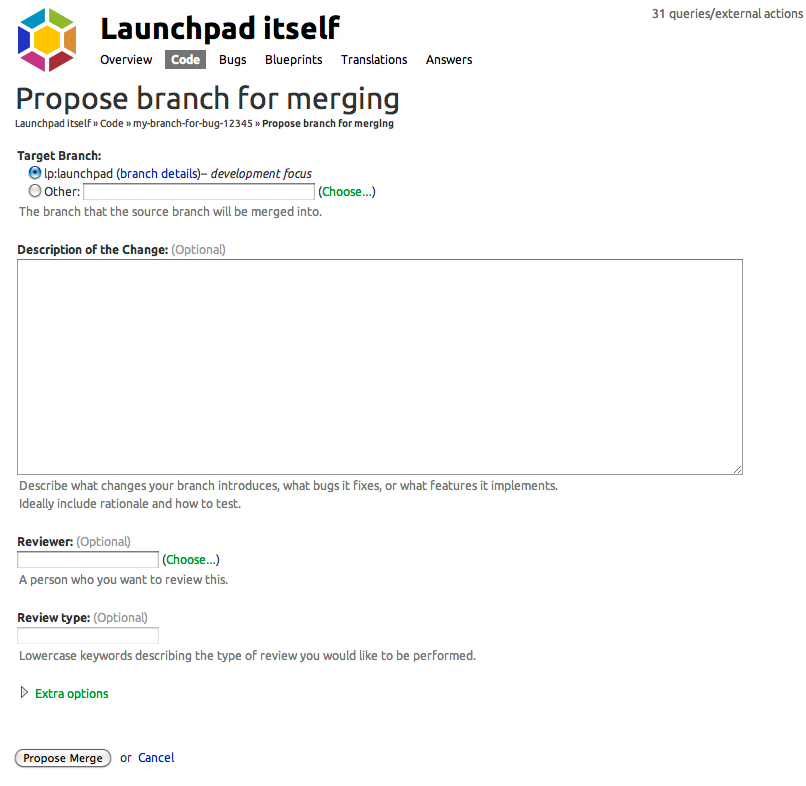

From the branch summary page, you need to create a merge proposal. To do this, click “Propose for merging.” You’ll be presented with this page:

On this page, you’re going to explain what you’ve changed and why. There’s a template for what we refer to as the merge proposal cover letter on the Launchpad dev wiki.

Things you absolutely must include in your cover letter:

- A summary of the problem.

- A summary of your proposed solution.

- Details of your solution’s implementation.

- Instructions on how to test your solution and how to QA it.

Launchpad Clinic – UDS

At UDS-Q we’re going to run two day with the help of Graham Binns who will be there to help with hands on set up and walk people through their bugs they would like to work on and figure out where to start. If you’re interested in taking part in these sessions, please add your name and the bug(s) you are interested in so we can review them ahead of time, there are many to chose from that are tagged with trivial if you want to start there.

We will have a EC2 instance set up of Launchpad to maxamise the time available to work on these areas.