Who’s using the Launchpad API?

Published by Karl Fogel March 31, 2009 in API

People are starting to integrate Launchpad into applications, talking to it directly through its API — either by using the launchpadlib Python library or by doing RESTful HTTP requests.

Below are some of the uses we’ve found — if you know of some not on this list, please tell us (in the comments here is fine). This is partly to help us see what areas of the API are getting the most mileage, and partly because this collection might be a good resource for people who want example code for using the Launchpad API themselves.

(Note: we’ve now collected this information into a Launchpad API Usage directory, and will maintain the list there from now on.)

-

bzr-eclipse, a Bazaar plugin for Eclipse, that talks to the Launchpad/Bazaar integration using launchpadlib. The developer says: “The API is straightforward to learn, also if you can use launchpadlib it’s far easier, just start the python interactive interpreter, import launchpadlib and start prototyping your app :)”

-

Tarmac, “The Launchpad Landing Strip”: an automatic branch lander for the Bazaar branches hosted on Launchpad. Tarmac uses the Launchpad API to manage a development focus branch’s proposed merges. It will automatically merge approved branch merge proposals and push them back up to Launchpad.

-

apport, a crash detection system that automatically generates reports with debugging information from crashed programs and provides UI frontends for handling these reports. Apport uses launchpadlib in a script (apport-collect) that adds apport data to existing bug reports.

-

ubuntu-dev-tools, a collection of useful tools that Ubuntu developers use to make their packaging work a lot easier (bug filing, packaging preparation, package analysis, etc). Ubuntu Dev Tools uses launchpadlib in the manage-credentials, requestsync, massfile, lp-set-dup, grab-attachments, and hugdaylist scripts. They’re all sharing the ubuntutools/lp/libsupport.py library, which might be a good place to start.

-

ubuntu-qa-tools, a collection of tools used by the Ubuntu QA Team (sort of parallel to ubuntu-dev-tools, but for QA). See the ml-fixes-report.py, ml-team-fixes-report.py, b-tool, package-bugs-gravity.py, team-reported-bug-tasks.py, and team-assigned-bug-tasks.py scripts.

-

ilaunchpad-shell, an interactive shell to Launchpad.net.

See also the API category on the Launchpad Blog, which has posts with code examples, news, etc. And this thread on the Launchpad Users mailing list may accumulate more examples, even after this blog post goes up.

Launchpad maintenance 27th March and 1st April

Published by Matthew Revell March 24, 2009 in Notifications

We have some planned maintenance and the release of a new version of Launchpad coming up, both of which will mean a short period of down-time.

PPAs offline for 30 minutes on the 27th of March

Important update: We originally announced the PPA down-time as happening on the 26th March. Due to some scheduling conflicts, we have moved the PPA down-time to Friday 27th March.

We’re upgrading one of the servers we use to provide Personal Package Archives, which will result in 30 minutes of down time on Friday 27th March.

Going offline: 16.00 UTC 27th March

Expected back: 16.30 UTC 27th March

During that time, you’ll be unable to upload to or download from Personal Package Archives.

Launchpad offline for one hour on the 1st of April

We’re releasing the latest version of Launchpad — 2.2.3 — on the 1st of April. All of Launchpad will be offline for around an hour while we roll-out the new code to our servers.

Going offline: 22.00 UTC 1st April

Expected back: 23.00 UTC 1st April

Linking project releases in Launchpad to milestones

Published by Curtis Hovey in Coming changes, Projects

In our 2.2.3 release of Launchpad — due 1st of April — we’re strengthening the relationship between milestones and releases.

Project releases will be explicitly linked to a milestone, meaning the release inherits the milestone’s series and identity information.

You’ll be able to create a new release from a milestone page or, if you don’t yet have a milestone, there’ll be an option to create a release and its parent milestone simultaneously. You can still have milestones that do not correspond to releases.

Just as now, the release will hold the release notes, changelog, date released, and any downloadable files.

What are Releases, Milestones, and Series?

Launchpad hosted projects can arrange their development into Series, which contain Milestones to which bugs can be targeted, and Releases which hold download tarballs and have release notes. Although Milestones and Releases go together, they were previously managed separately in Launchpad. Now they’re more unified.

Why are we doing this?

Many people already use releases and milestones in this way. Milestones aid release planning, and help people understand a project’s goals. Creating a release directly from a milestone implies that the milestone was reached.

Linking milestones to releases improves the data consistency between projects. With good milestone and release information, Launchpad can improve the presentation of series to explain what has happened, and what will happen. We hope that this will make it easier for people to know where and when to make contributions to your project.

This change also allows us to redesign the series, milestone, and release pages. Our goal is to better present the history and future of a project, as well as to improve the workflow for planners.

What you can do

You do not need to take any action regarding releases. We’re migrating existing releases by linking them to a milestone, or if there isn’t an appropriate milestone, creating a new one.

You can use Launchpad’s staging environment — https://staging.launchpad.net/ — right now to check what your releases

and milestones will look like under the new system.

We’d value your feedback so we can improve the data migration script. If you come across a problem, please report a bug here:

https://bugs.launchpad.net/launchpad

For other comments, send us an email to feedback@launchpad.net

How we’re making the migration

The release’s project, project series, version, code name, and summary come from the milestone it’s linked to. The release’s version will come from the milestone’s name.

When a release and a milestone share the same series and version/name, they are linked. The release’s summary will be appended to the milestone’s summary. You should review your project’s milestones. You can make changes to your project’s milestones and releases on launchpad.net to ensure they are merged correctly on staging.launchpad.net before the final migration.

When no milestone can be matched to a release, a new milestones is created from the release’s information. The milestone is not active, they will only appear on the project’s milestone page. There are a few instances where two series have a release of the same name. Milestone names are unique across a project. So the milestone’s name will contain the release’s version and series name (0.9-series-trunk). You can prevent this from happening by renaming some of your project’s releases on launchpad.net now — in most cases, the duplicate release name is on an obsolete series, or trunk. You can view all your projects series at:

https://launchpad.net/<your-project>/+series

We’re also taking the opportunity to rename a couple of things: description” becomes “summary” and the milestone’s visibility flag (in the REST API) is renamed to “active”.

We believe this change will make releases and milestones much more useful. Please do report bugs or email us if you have any comments.

Gmail filters for Launchpad bug email

Published by Matthew Nuzum March 13, 2009 in Bug Tracking

I get three kinds of email from Launchpad generally:

- Regarding bugs I’ve reported or specifically subscribed to

- Those assigned to a team I’m a member of

- A very occasional question or notification about a code branch I’m subscribed to.

Of these above the second is the most voluminous and the first group is the most important. However sometimes items from group two can be important, depending on the project. Launchpad includes headers for filtering email which I’ve used in Thunderbird. I’ve not been able to create sophisticated filters in Gmail though. Until now.

In the past I just grouped all Launchpad email into a folder. This folder fills up very quickly though and it becomes a burden to identify which items need my action and decreases the effectiveness of Launchpad’s bug tracking. By creating a Gmail label for different kinds of bug email I can better attend to the messages in the proper order.

Here’s my set-up: I use Evolution to access Gmail via IMAP during the work day. Otherwise I use the Gmail web interface. I want the filtering to happen all the time so I use Gmail’s filtering, not Evolution’s. This limits our capabilities significantly. Well, maybe not … read on. 🙂

The trick is to look at the emails for something that Gmail can search on and are constant among emails you want to group by. This prevents us from using the subject or the sender or the recipient. :-/

My end result is to have a label for bugs assigned to or reported by me (including bugs I’ve subscribed to) and one label for each group or project I’ll get bug notifications from. I’m naming the labels Bugs/me, Bugs/artteam (for the Ubuntu Art Team), Bugs/website (for the Ubuntu website) and etc.

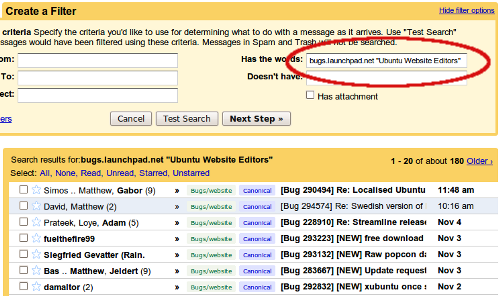

I found that all bug email is shown if I search for bugs.launchpad.net. So I’ll use it for all of my searches. I also noticed that the bottom of each email tells me why I got the message. For example, “You have received this email because you are a member of the group Ubuntu Website Editors.” That is the key. Therefore I can do a search like this:

bugs.launchpad.net "Ubuntu Website Editors"

This will show me all of the bugs for that team. I can then create a filter and put that search string in the “Has the words:” field and do a test search.

We’re set. I click next and set the rules:

"Skip the inbox" is checked

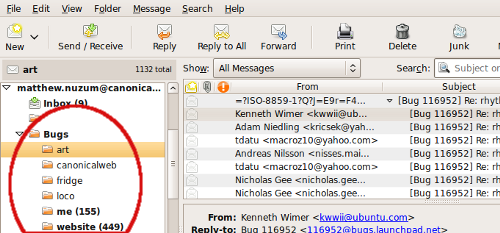

"Apply the label" -> Choose "new label" -> Name my new label Bugs/website

"Also apply filter to x conversations below" is checked

Then I click “create filter.” The interesting thing above that I’ve not mentioned yet is the label I chose. By creating a label with a / in it then when accessed via IMAP it will appear as a folder. So if I go on to create labels called Bugs/artteam and Bugs/me my IMAP client will show a “bugs” folder with three sub folders.

Speaking of Bugs/me, this filter is different than the others. The search string I used here is:

bugs.launchpad.net ("direct subscriber" | "bug assignee")

Any bug that gets assigned to me or to which I subscribe is put in the “me” folder. Because Gmail’s labels are different than true IMAP folders it means that some email threads will show up in multiple places.

I’ve only implemented this solution today so no long-term testing has been done yet, but already I’ve been able to burn through a huge backlog of bug emails simply by marking as read the bugs in entire folders and focusing my concentration on the “me” folder.

There are a few emails (about 20 in the last year or so) that didn’t get caught by the filter. A couple pre-date changes in the way Launchpad sends its emails. Others were related to “answers” and subscribed branches. The volume is so small that I foresee being able to deal with these special cases as they appear in my inbox. Maybe you have more of these special cases than I do. I hope that my explanations above are clear and you can adapt the solution to your own mailbox. Feel free to leave comments about your adaptations so that others can benefit from them.

**Bonus tip:

Do you use Gmail all the time? If so you can have your labels appear as folders that can be expanded and collapsed, just like in an IMAP email client. There are two ways to accomplish this, the simplest to install is the “Better Gmail 2” extension for Firefox, the other is the “Folders4Gmail” Greasemonkey user script. “Better Gmail” is a compilation of stand-alone Greasemonkey user scripts including the Folders4Gmail package. I decided I didn’t need most of those features and already had Greasemonkey so use only the Folders4Gmail.

Inside the Launchpad AJAX Sprint: A Week with Widgets and YUI 3

Published by Maris Fogels in General

Recently ten people from Launchpad and other parts of Canonical came together in Berlin to hack on Launchpad’s new YUI 3 JavaScript interface. The sprint was tremendously successful, producing four fully functioning YUI 3 Widgets, complete with test suites and live demo pages. This post offers a look inside the event, and some thoughts about what made it so successful.

The sprint brought together one member from each of Launchpad’s teams, as well as Martin Albisetti, for his design insight, Francis Lacoste, for his Zope3 and Launchpad architecture knowledge, and Stuart Langridge, who, to our surprise and fortune, had much jQuery, DOM, and CSS experience. This wasn’t the team’s first encounter with the YUI 3 JavaScript library (we had spent two weeks in the fall reviewing JavaScript, YUI 3, and client-side development), but this would be our first time taking YUI 3, and Launchpad’s JavaScript support, up to full speed.

Martin kicked off the morning of day one with a walk through some video proof-of-concepts that we would bring to life. After some wide-ranging discussion and dealing over implementation details, we spent the afternoon looking at the technical side of YUI 3 Widgets. At the end of the day eight of the sprinters split into pairs, each pair picking a widget to work on.

Day two saw the four teams plan their attack, then dive into the code. The sprint took on the shape of a massive parallel experiment, with each team choosing a different development approach: one wrote tests first, diving into Test Driven Development; another executed a two-pronged assault, with one person writing the widget while the other worked on Lauchpad integration. A third team went for functionality first, aiming for a working wireframe before styling the page, or writing tests. In the end none of the approaches was a clear winner, but it’s worth noting that quickly getting a working prototype up on the projector gave everyone a huge moral boost, and looks to be worth the cost of that team writing their tests last.

One thing that helped every team get up and running quickly with the YUI 3 Widget framework was having an already-running, fully integrated widget in Launchpad: the inline-text editor for Bug and Project titles. Building the inline editor had cleared paths for coding styles, directory structure, test harnesses, and all of the Zope3 integration code. A month or two of work had already gone into supporting JavaScript and JavaScript testing in Launchpad — now that work paid off, giving all eight people a very fast ramp-up to code that could land in mainline. Along with the very well-written YUI 3 docs, everyone was writing code by noon.

Day three saw more code, tests, and our first working widget. We just needed the fancy frame to have a pixel-perfect movie match. The teams kept the momentum high all day while Martin, Francis and I criss-crossed the room, lending design decisions, on the spot integration plans, and YUI advice and council. Stuart Langridge also lent his scripting and CSS experience to the effort. For any sprint, when the team is blocked on an implementation question, it helps to have someone with the authority to make final, on the spot decisions. We discovered that, when doing top-to-bottom JavaScript widget implementation, it helps to have a whole team of them.

By noon of day four most of the remaining widgets were functional, if not fully styled. For me, much of the day was spent pair programming, tackling a subclass of the YUI Overlay widget. We had trouble getting it to accept the stylish drop-shadowed frame given to us by our designer, and we used YUI 3’s JavaScript unit testing library, yuitest, to work around it. Our test suite allowed us to spot the Firefox DOM bugs our layout triggered, and assured us that our hackish workarounds unbroke the DOM tree.

Most of the sprinters were qualified code reviewers, so day four’s afternoon was spent in a team review of the fully functional fancy Overlay widget: two authors presenting with Emacs, one scribe, and seven people contributing questions and comments. The meeting helped immensely in building a culture around JavaScript code in Launchpad, and left us with a draft JavaScript style guide, and a coding standard we could take to the wider team. I highly recommend such a review, along with the surrounding discussion, to anyone bringing a new language into a programming group.

Everyone had great momentum going into day five. All four widgets were fully functional, with only a few rough spots remaining. One nasty Friday surprise was that the original inline editor didn’t work in Konqueror 4.1 — in fact, it made editing Launchpad Bug titles impossible. This is where our adoption of YUI’s Graded Browser Support and Graceful Degredation really shone. We quickly made the decision to give KHTML browsers a C-Grade experience: for them, the site behaves as if it were not enhanced with JavaScript: you can still edit a bug title, but you are taken to a new page to do so. The decision was fast and simple, and with a clear C-Grade verdict of “No JavaScript”, no unnecessary time was spent searching for other fun issues the browser may have presented.

Day five’s afternoon was spent with everyone in a Review Jam. We mixed up the programming pairs, with one person from each team reviewing someone else’s code, using the guidelines we had drafted the previous day. Martin did some final user interface design reviews, and everyone left that Friday with a list of changes before final submission to mainline.

The sprint was very successful, one of our best yet, producing four YUI 3 widgets in only three and-a-half days of coding, and we plan to have another sprint like this in the future. Here’s some of what made this week-long coding sprint work for us:

- You need to have a good mix of skills at the sprint, including experienced people from each discipline. And that experience needs to be available to unblock sprinters as quickly as possible. At this sprint, two of the ten people were dedicated to roaming the room, and at least two more had deep experience with the problems we were tackling.

- Someone at the sprint needs to be a project stakeholder, with desicion-making authority. They’ll be called upon as the sprint progresses. Martin filled this role for us, having final authority on what the Launchpad user interface would look like.

- If sprinters are building something new, but understood, come prepared with a template, plan, or example that everyone can follow. Use that template to spend less time at the sprint understanding known problems, and more time tackling new ones. The completely integrated and running inline editor widget had already covered all aspects of widget development for us.

- Sprinters do very well with self-selected goals and self-made plans. We didn’t hold any of the teams to any particular approach (aside from some good-hearted chiding about unwritten tests), which let everyone adapt their style to their own problem. Two of the teams even picked goals that were more ambitious than the original scope.

A final word on YUI 3: the library performed very well, especially given its pre-release status. Experienced scripters may find working with YUI 3 a little odd at first, because you are not working with the raw DOM: you have to get used to using YUI Node instances, getters, and setters, instead of DOM object properties (most of the DOM methods are passed right through). However, once past the initial bump, you can quickly see the advantages of having features like object property getters and setters, a robust and advanced object construction system, and cross-browser APIs. Stuart also pointed out one big, open question about YUI itself: the only major libraries to tackle JavaScript widget development “in the large” are YUI and Dojo. We’ll see if YUI’s large approach, jQuery’s small tools approach, or YUI 3’s mix of both is best.

Shutter

Published by Matthew Revell March 11, 2009 in Projects

Screenshots are screenshots, right? If whacking the “Print Screen” button doesn’t offer enough refinement, then surely firing up The Gimp, gnome-screenshot or knsapshot would give you what you need, wouldn’t it?

Screenshots are screenshots, right? If whacking the “Print Screen” button doesn’t offer enough refinement, then surely firing up The Gimp, gnome-screenshot or knsapshot would give you what you need, wouldn’t it?

The team behind Shutter would disagree. I was interested to know what would motivate someone to develop a new screenshot app, so I asked Mario Kemper why he began work on Shutter.

Mario: Well, I am a computer science student working as QA person in my freetime. When i started to do the QA work I was looking for a neat screenshot application because we are doing a lot of documentation for the developers as well.

There were some apps like ksnapshot, gnome-screenshot etc. but they all focus on a single screenshot; no editing features, no session, no nice effects etc. So i started to develop Shutter (formerly gscrot) with these features and goals in mind.

There is another big point, though: we all spend much of our time in forums, wikis, chats etc. From time to time we need to do some screenshots and upload them so we can share them with other people so i wanted to have a built-in function to upload your screenshot with nice link-formatting so you can post the generated link directly in the forum, wiki etc.

Shutter uses Launchpad for bugs, code, translations, answers and blueprints. You can get hold of Shutter from the Shutter team’s Personal Package Archive.

Why PyRoom chose Launchpad

Published by Matthew Revell March 4, 2009 in Projects

Perhaps shutting out the distractions of the physical world is no longer enough.

Perhaps shutting out the distractions of the physical world is no longer enough.

PyRoom is a simple text editor that shuts out all the distractions you might find in a more complex editor or word processor, giving you nothing but a black screen that you can type into.

Bruno Bord has driven the project and chose Launchpad to host it. I asked him what led him to choose Launchpad.

Short answer: Because I was lazy, and I didn’t want to hack on a project management system myself. Launchpad hosts everything I wanted: code, bugs, translations.

Long answer: It’s not just the bug tracker. It’s the whole thing. Bug trackers are very interesting to track down tasks, reorder them, assign them priorities, etc. But it’s like playing all alone on a video game while you could have much more fun playing it online, with other people

involved.I discovered Code Versioning System and then moved to Subversion, which was a massive improvement. When I had to download a source code from CVS, I used to copy-paste command lines I didn’t understand into a bash script, and run it from time to time to update my working copy. I’ve never used CVS as a committer, and I’m glad.

I was working in a small web agency where the “revision” system was just renaming the old version of a file/directory “_old”, make a copy of it, and go on with the developement. Of course, when there was another “revision” to “commit”, you had to rename it “_old2”. Hem. Pretty amazing how things can become hellish using that kind of system.

I heard about Subversion, and reading the docs, I instantly fell in love with the syntax. At last, I could version my work with commands I could grok!

I made a quick svn+trac install on our local server, and that was ready. One of the major drawbacks of Trac at the time was the impossibility to track several projects at once.

So I had to build up a trac instance for every new project. Which was fine, as soon as I could make a tiny bash script that did everything from the ground up (svn repository and trac setup).

Anyway. I started using SVN for my personal projects. A friend of mine accepted to host my trac+svn instance for pet projects on his personal web server, and everything was fine.

One day, I moved. And I went off the internet at home for 149 days. Yes. It’s a huge number of days for a geek. At work, it was ok, but it was impossible for me to commit changes about my pet projects.

After months of despair, I finally found out about Distributed Version Control. And bzr changed my life. I could work on my projects offline, commit code, branch, merge, etc, and push it back again in the main repository when internet connection came back — this is true for any DCVS, not only bzr…

But bzr isn’t very well integrated into Trac (yet). And it’s fully integrated with Launchpad.

What’s absolutely brilliant in Launchpad is the fact that any item may interact with another. You can register a branch in a project, or in your “+junk” repository, or you can link a bug to a branch or link a branch to a bug. Once the bug is fixed, you propose the branch for merging. You can build up teams, working on specific tasks on your project: bugsquad to sort out bugs, developers to commit in the main branches, translators, or a just more general team where people interested by the project can get notifcations at any time.

Hence, using LP as a project manager makes sense.

Using LP for PyRoom was an instant choice. When I retrieved the initial python script from ubuntuforums, I commited it into a bzr branch, hacked on it a bit to clean up the code, and pushed it on the fresh new project hosted on LP.

I learned a lot during the first weeks of the project: one of the best practises is to create teams. You are on your own at the beginning, but create a team anyway, and give this team read/write access to the trunk of the project. When people start to get involved, they join the team, and are granted instant access on the main branches of the project.

But the good thing with LP is that you don’t actually NEED to be part of the dev team to send code. For Gwibber, for example, I just hacked on a bug I found with my French locale the main developers couldn’t guess. I just registered a bug, created a branch, pushed my code to this branch, and proposed it for merging. It was merged without me being member of the Gwibber team or whatever. Now the bug may be closed. WIN!

My first contributions in LP were translations, IIRC (into French, what a surprise!). Again, I was not member of any team to translate small strings in my mother tongue.

You see… it’s not just the bug tracker. Any text editor can work as a bug tracker, as long as you keep your tasks up to date in a single file. It’s the whole shebang that rocks.

Translations team in Buenos Aires

Published by Matthew Revell in Translations

I’m in Buenos Aires this week with the Launchpad Translations team — Danilo, Jeroen and Henning — along with Launchpad UI guy Martin Albisetti.

I’m in Buenos Aires this week with the Launchpad Translations team — Danilo, Jeroen and Henning — along with Launchpad UI guy Martin Albisetti.

We’re working on making Launchpad cleverer at giving people the information they need where they need it. Each day we’ve been sitting with a white board, a list of existing pages that we want to improve and one simple question: what do translators want from that page?

And that’s a question that we can answer through the feedback that we’ve had on how translation can work better and also the translations that we’ve made ourselves.

We’re half way through the week and have some great plans that you can expect to see in place before our 3.0 release in July.

Inside the Launchpad Foundations sprint

Published by Leonard Richardson March 3, 2009 in API

I’m in Montreal this week, with the rest of the Launchpad Foundations team and a few other Canonical engineers. We’re preparing for the open sourcing of Launchpad by doing a lot of refactoring, so that when the code is released in July it will be more comprehensible, and reusable in projects other than Launchpad.

In addition to our main body of Launchpad code we’ll be releasing a framework project called LAZR. Code that’s not Launchpad-related will go into LAZR or one of its subprojects: lazr.config, lazr.uri, lazr.batchnavigator, and so on. These will be little libraries that can be reused in other projects.

For instance: underneath the Launchpad web service is a generic library that lets you create a web service from your existing data objects by annotating the Zope interfaces. All this code lives in LAZR: the only web service code in Launchpad has to do with Launchpad’s web service specifically. We’d like you to reuse the LAZR webservice code in any project that uses Zope interfaces to describe its data objects.

Unfortunately, there’s a lot of code in Launchpad that really should be in LAZR. If that wasn’t bad enough, the web service code in LAZR is full of dependencies on that Launchpad code. At the moment, you can’t run the LAZR web service code without bringing in all of Launchpad.

The object of this sprint is to refactor this code and move it all into LAZR packages. Our medium-term goal is a working example web service (code name “Sharks”) that uses no Launchpad code, but it won’t stop there. The more utilities we can move out of Launchpad’s monolithic code base, the more likely it is you’ll be able to find a bit of code you want to reuse.

Meet Jeroen Vermeulen

Published by Matthew Revell February 27, 2009 in Meet the devs

Jeroen Vermeulen gives us our first Asian stop-off in the Meet the devs series.

Jeroen Vermeulen gives us our first Asian stop-off in the Meet the devs series.

Matthew: What do you do on the Launchpad team?

Jeroen: I work on the Translations application. That’s where we translate software (including all of Ubuntu’s “main” section!) from English into just about any language I’ve ever heard of. Many people still know it by its original name, Rosetta.

Matthew: Can we see something in Launchpad that you’ve worked on?

Jeroen: It’s a funny thing: that question makes me realize how little really “visible” stuff I’ve written. I’ve been working with the database a lot and of course fixed bugs. You could say there’s mostly things that you can’t see in Launchpad that I worked on.

Recently though I’ve been working on something you should see show up in more places soon: the inline text editor. If you have javascript enabled in your browser, you can already use the existing version when you edit a bug title. No need to click through to an editing form: you just click the “edit” icon and the title becomes editable in-place.

The version I’ve been working on together with Danilo Šegan (I found out how to type that weird letter by accident:

It’s been both fun and a nuisance, since JavaScript lets you do very powerful stuff very quickly… and then it lets you spend days debugging the silliest little things. It’s a far cry from the C++ work I’ve been doing in my spare time. There, all your weak typing happens at compile time. At run time it’s all strong typing with a tiny bit of polymorphism. So it’s usually the compiler that spots the bugs, not your tests per se. As the language matured we grew habits and practices to reinforce this. Nowadays I barely even use polymorphism anymore in C++: only in a handful of isolated patterns, and more often than not purely at compile time. As my friend Kirit Sælensminde puts it, it’s great to have a compiler as a theorem prover for your code’s correctness!

Matthew: Where do you work?

Jeroen: Mostly in Bangkok, Thailand. I like to poke fun at my colleagues in places that are 40°C colder.

Matthew: What can you see from your office window?

Jeroen: One of the reasons why I picked the place: some green, unused land! It’s got grass, trees, birds, and not a whole lot of noise. That’s pretty rare in this city. What there is is usually hidden behind walls.

Right under my window there’s a dirt road with a volleyball net strung across it. Sometimes the children have to stop playing and lift the net to let a car pass underneath.

Matthew: What did you do before working at Canonical?

Jeroen: I worked for a Thai government department set up to promote open-source software in the country. It was a good chance to learn, both about technology and about cultures.

Nothing shows how the two can interact as well as the questions I got at trade shows. For instance, many people believed that software you give away cannot possibly have any value. To those people I had to explain how the software made money for the companies behind them, or they just wouldn’t consider using it. This in a country where pirated proprietary software is the norm, and price-competitive with free downloads.

Other people thought that “open source” and “linux” were the same thing, and were very sceptical when you showed them free software running on Windows. Those who do work on free software, and we have some very enthusiastic people doing that, tend to be a bit too shy for the process. They are often reluctant to badger authors about accepting patches or translations. Translating Ubuntu in Launchpad is a great way for them to get around that.

Matthew: How did you get into free software?

Jeroen: Mainly by not staying out of it. When I started programming for fun in the early 1980s, the only reasons my friends and I ever saw not to share our code were embarrassment (if the code was ugly) or fear of someone passing it off as their own (if the code was pretty). But most of the credit goes to some great people I met in and after university, and a company called Cistron that got me working with 100% free software professionally.

I did work a few jobs involving proprietary software, and some of those left a very bad taste in my mouth. At Cistron we sometimes had to patch the software we used, because it wasn’t always mature. But at least we could, and we’d be helping the software mature in the process. We didn’t need to ask for permission, or wait for someone who already had our money to decide whether our problem was a priority. In the proprietary world you always had to beg or wait for permission to solve some problem or other.

Surprisingly often, it’s easier and cheaper to deal with a problem yourself than to go through the process of getting proprietary software licenses for it. That’s even before you start handing over money. If you do make it past that, you come to the stage where you start seeing the little gaps between what you bought and what you needed. And then you end up coding your own in-house glue anyway.

There was a lot of the code as well, under the glitzy surface. Oh, the code! Some examples I’ve seen:

- A button in a user interface switches the application between two modes. The button changes its label and its colour between modes. The business logic decides which mode it’s in by looking up the button’s current colour. Yes, you read that right. This is in a large-scale financial application. The code was then given to cheaper foreign engineers for maintenance, despite all the comments, identifiers etc. being in the local language and unreadable to the engineers. The maintenance was necessary because the application relied on some proprietary commercial infrastructure that was being end-of-lifed by its vendor.

- A database table has three consecutive rows for every logical item it describes. A loop searches them linearly instead of using SQL’s WHERE clause. Instead of using a meaningful marker, the loop computes what row #i represents by taking i % 3. The switch statement has cases for 0, 1, 2, and “default.” It’s been a while but I seem to remember there was a case for 3 as well.

- A database object cache looks if the object you requested is already in memory. It does so by taking the numeric id for the object you want and comparing it to each of the cached objects’ addresses. It never finds a match because in-memory addresses simply have nothing to do with identifiers in the database. The problem goes unnoticed for years (causing memory leaks and data loss) because the compiler, also proprietary, takes until version 5.0 to start noticing that this is a very basic type error.

It’s not like we don’t make those mistakes in free software. But we let people catch us at it, and it’s better for everyone. In fact I’m convinced that projects like Linux and MySQL became so popular in part because there were enough things for beginning contributors to fix.

Matthew: What’s more important? Principle or pragmatism?

Jeroen: You’re eating soup. The bowl breaks. (Not likely, but work with me here). Now tell me which was more important: the bowl or the soup?

I know a lot of people get very worked up about this. But principle and pragmatism are on a two-way street. Going one way, principle is where you look when deciding what you should do. Or, and this is usually what gets people worked up, what everyone should do. But going the other way, you look at pragmatic reality and discern all sorts of principles. That, I think, is the real attractor to the whole debate &mash; free software has basically revived classical philosophy. What you learn there, what catches your imagination, what patterns you see and choose to explore, is all very personal.

There are people like Eric Raymond who will say that everyone just does what’s in their best interest, and nothing else will decide the course of events. The big epiphany they take from the free/open-source development is game theory and how it applies to markets. Then there are people like Richard Stallman who see how the given incentives in the market pit us against each other, and decide that it’s a bad thing. They derive a field-specific model of morality. Personally I’m fascinated by both.

But enough weaseling: I’m more on the “principle” side, because I don’t think principles are inherently non-practical. One of the smartest people I’ve known once said that morality evolves. It grows and adapts to help us survive as a group, just like perspective vision or opposable thumbs. Software licensing is at a point where different people try different things and we’re seeing what works. If I “sell” you software, it has to be like a piece of property, except copying is free and unlimited. So should we pretend that the program is still “my property” after the sale, only I’m also letting you use it? Or is it now yours, except I can sell it to others as well? It’s a lot like the old particle-or-wave debate about the nature of light.

Matthew: Do you/have you contribute(d) to any free software projects?

Jeroen: In all sorts of ways, usually to scratch an itch: a patch here, some documentation there. My main project is libpqxx, the C++ client API to PostgreSQL. I worked with the old API back in 2000, and it was as if the right approach just jumped at me, shouting “code me, code me!” I get a lot of positive feedback about how it blends in with the language and its standard library.

Sometimes you can do more good by documenting than by coding. We engineers are all the same: once you understand something, it’s “obvious” and suddenly you’re unable to explain it. I thought D-Bus was a great development when I first saw it, but the documentation was thin on concepts and too detailed. Since I had to figure out the concepts anyway, I made a list and pretty soon I had a decent introduction written up. It even sparked some debate between developers about unresolved design questions. Funny how a contribution like that is easier to make when you’re new to the project. Much the same happened with fcgi, a nice “persistent CGI handler” similar to FastCGI but much simpler.

Matthew: Tell us something really cool about Launchpad that not enough people know about.

Jeroen: My personal favourite is a very basic one that we’ve had for ages: because Launchpad mirrors subversion and CVS repositories, you can play with the code of some project and still have full revision control.

When I wanted to mess around with a piece of code I got from the internet, I used to download a tarball, unpack, work on the code, then diff against a freshly-unpacked copy. Or I’d check out the repository and never commit. But now I can just branch off Launchpad’s copy of the source tree, and commit changes locally to my own branch.

Matthew: What’s your favourite TLA?

Jeroen: Hard one, since I have over 23,000 to choose from! I keep them here.

It started out as a joke about TLA-space pollution, but some people actually use it as a reference. I do, too.

What’s my favourite TLA? I like the name of the list itself, which is a meta-TLA. GTF stands for GPL’ed TLA FAQ. If you send me a new entry you become part of the GTF Contributor Program or GCP, and you get a little logo you can show on your home page.

Matthew: Okay, Kiko‘s special question! You’re at your computer, you reach for your wallet: what are you most likely to be doing?

Jeroen:Probably checking for a 10-Baht coin so I can get a motorcycle ride back to the main road. The dogs get a little frisky sometimes, so the wild ride may be marginally safer. The coin looks just like a worn 2-euro coin at about 1/10th the price. They’re similar enough that many coin slot machines had to be recalibrated.

Matthew: Thanks Jeroen!