Today we’re announcing early support for hosting Git repositories directly on Launchpad, as well as or instead of Bazaar branches. This has been by far the single most commonly requested feature from Launchpad code hosting for a long time; we’ve been working hard on it for several months now, and we’re very happy to be able to release it for general use.

This is distinct from the facility to import code from Git (and some other systems) into Bazaar that Launchpad has included for many years. Code imports are useful to aggregate information from all over the free software ecosystem in a unified way, which has always been one of the primary goals of Launchpad, and in the future we may add the facility to import code into Git as well. However, what we’re releasing today is native support: you can use git push to upload code to Launchpad, and your users and collaborators can use git clone to download it, in the same kind of way that you can with any Git server.

Our support is still in its early stages, and we still have several features to add to bring it up to parity with Bazaar hosting in Launchpad, as well as generally making it easier and more pleasant to use. We’ve released it before it’s completely polished because many people are clamouring to be able to use it and we’re ready to let you all do so. From here on in, we’ll be adding features, applying polish, and fixing bugs using Launchpad’s normal iterative deployment process: changes will be rolled out to production once they’re ready, so you’ll see the UI gradually improving over time.

What’s supported?

You can:

- push Git repositories to Launchpad over SSH

- clone repositories over git://, SSH, or HTTPS

- see summary information on repositories and the branches they contain in the Launchpad web UI

- follow links from the Launchpad web UI to a full-featured code browser (cgit)

- push and clone private repositories, if you have a commercial subscription to Launchpad

- propose merges from one branch to another, including in a different repository, provided that they are against the same project or package

What will be supported later?

Launchpad’s Bazaar support has grown many features over the years, and it will take some time to bring our Git support up to full parity with it and beyond. Git repositories use a somewhat different model from Bazaar branches, which we’ve had to account for in many places, and some facilities will require complete reimplementation before we can support them with Git.

Here’s an incomplete list of some of the features we hope to add:

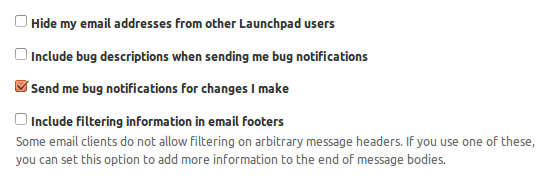

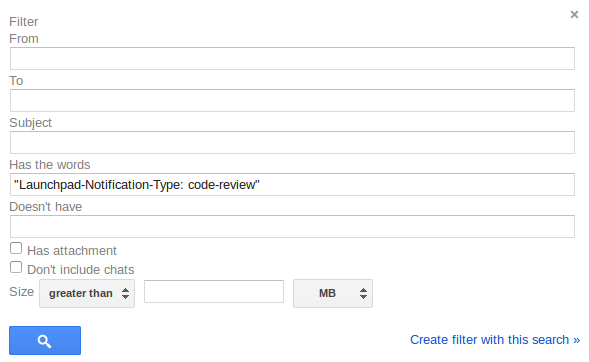

- useful subscriptions (currently only attribute change notifications work, which are not usually very interesting in themselves)

- RSS feeds

- mirroring

- webhooks

- an integrated code browser

See our help page for more known issues and instructions on using Launchpad with Git.

Helping out

This is a new service, and we welcome your feedback: you can ask questions in #launchpad on freenode IRC, on our launchpad-users mailing list, or on Launchpad Answers, and if you find a bug then please tell us about that too.

Launchpad is free software, licensed under the GNU AGPLv3. We’d be very happy to mentor people who want to help out with parts of this service, or to build things on top of it using our published API. Some preliminary documentation on this is on our developer wiki, and you can always contact us for help.